Image: Mark Hachman / IDG

Image: Mark Hachman / IDG

PC vendors and chipmakers are eager to make your next PC an “always connected PC,” with built-in cellular connectivity ready to step in when Wi-Fi isn’t available. It all sounds great on paper, but one question remains unanswered: How much will you have to pay?

The basic premise is simple enough: Open your PC, and boom! you’re connected to a cellular data network. It worked for the original Google Chromebook Pixel, and for many corporate PC users whose employers foot the tab. But now, helped by chipmakers Qualcomm, AMD, and Intel, as well as some early partners like Asus and HP, the PC industry seems poised to bring connected PCs to mainstream consumers using an “eSIM” model that allows them to buy data from any carrier.

Qualcomm leads on always-connected PCs

The engine driving always-connected PCs, surprisingly, isn’t Intel—though Intel has begun publicly maneuvering to respond. Instead, smartphone chipmaker Qualcomm used its recent Snapdragon Technology Forum in Hawaii to explain how it plans to break with the traditional metrics of price and performance to push an alternative: connectivity and battery life.

Qualcomm plans to take the Snapdragon 835 (and, though, it didn’t announce it at the time, the Snapdragon 845 as well) and make them the foundation of a new breed of always-connected PCs. The new Snapdragon Mobile PC Platform offers all-day battery life (from about 22 hours or so of active use to a couple of days’ worth) and instant connectivity through the integrated LTE modem.

Qualcomm is betting that consumers will prefer long-lasting PCs at the cost of some performance. It’s a somewhat risky tradeoff, but one that hundreds of millions of smartphone users have already adopted.

Three PC vendors are already in: Asus announced the Asus NovaGo ultrabook at $599 and above, and HP revealed the Envy x2 Windows tablet for an undisclosed price. A Lenovo always-connected PC will be announced at CES, Qualcomm executives said.

Qualcomm executives said they expect Snapdragon PCs will be manufactured by traditional smartphone vendors as well. In some sense, that’s already happened, said Asus chief executive Jerry Shen. “Asus has a history of designing beautiful devices for both the PC and smartphone,” he said. “We are well positioned to bring to life the benefits of LTE.”

Terry Myerson, executive vice president of the Windows and Devices Group at Microsoft, recalled how he didn’t plug in a Snapdragon-powered PC for a week. “I’m seamlessly connected wherever I am: at work, commuting, visiting a customer at a hotel, at the airport—I’m always connected,” he said. “It feels like the natural way to work with all of my team, all of my partners.”

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGThe HP Envy x2 is one of two Qualcomm Snapdragon PCs showed off last week.

Microsoft helps along Intel, too

Given its attendance at the Qualcomm event, Microsoft seems to view always-connected PCs as a sort of target of opportunity: More PCs mean more Windows licenses, and potentially more revenue. Microsoft’s dabbled in connected PCs with an LTE version of its Surface Pro tablet, but now seems ready to usher along the rest of the industry, too.

At its Taiwan Windows Hardware Engineering (WinHEC) conference in early December, however, Microsoft began putting its own spin on always-connected PCs. It introduced the concept of Modern Standby, referring to a PC that essentially remains connected to the Internet (either via WiFi or cellular) even while the PC is asleep. To enable this, Microsoft plans to add support for eSIMs to the next version of Windows, due sometime in spring 2018.

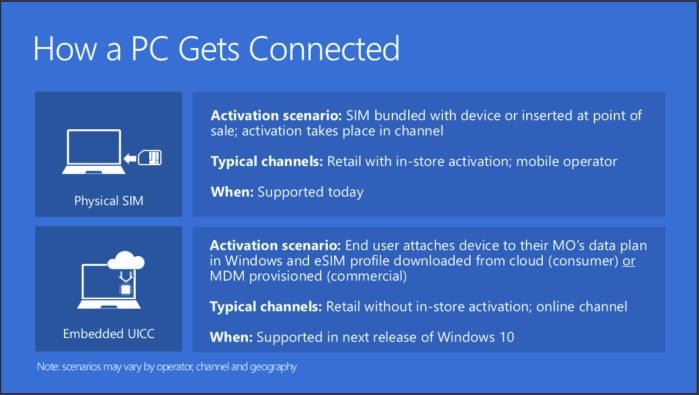

The eSIM is a new twist on the SIM card you’re already used to using with smartphones. As a Microsoft presentation at WinHEC noted, SIM cards today are usually bundled with the laptop (or smartphone) at the time of purchase, configured at the store, and are unable to be changed later without physically swapping out the tiny card. On the other hand, eSIMs are built right into the device itself, but the profile—whose carrier it’s assigned to, basically—can be purchased online and downloaded right to the card. It’s much more convenient than trucking a PC or a phone to a store for the carrier to configure it.

Microsoft

MicrosoftMicrosoft says eSIM support for always-connected PCs is coming. (Originally reported by the Walking Cat Twitter account, and then by ZDNet’s Mary Jo Foley.)

The goal is to enable “friction-free connectivity on all Windows devices at all times for consumer and commercial customers,” the presentation says.

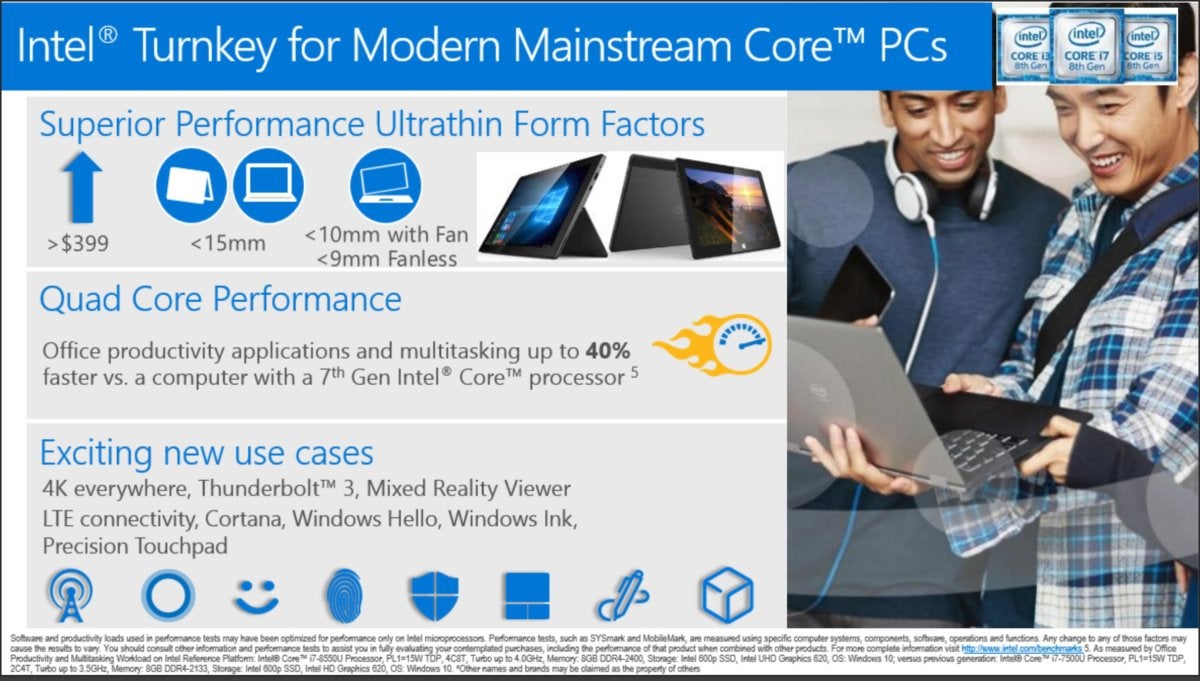

Intel still seems to believe in raw performance as the PC’s selling point. But one concession to the concept of an always-connected PC are eSIM provisions within two turnkey designs that its hardware partners could take and adapt for 2018: a “modern entry PC,” and a “modern mainstream Core PC.”

The modern entry PC design, Intel said, could be priced from between $199 to $399, with a 15mm thickness and a 4K display, and include either Celeron or Pentium chips offering 30-percent faster CPU and graphics compared to the prior generation. The mainstream Core PC, priced at $399 and above, includes an 8th-gen Core processor, 4K graphics, and Thunderbolt 3 I/O inside a sub-15mm ultrabook or 10mm tablet. Both designs included LTE connectivity.

Microsoft

MicrosoftIntel’s turnkey designs for PCs include support for LTE connections.

Intel hasn’t had much luck with integrating its discrete modems into cellular phones, but it’s been more favorable to a notebook or tablet where there’s enough room for the M.2 WWAN card it plans for its own designs. It’s not clear which cellular WWAN chip will be used, however, as Intel said in November that its recently-announced XMM 7660 Cat-19 LTE chip wouldn’t ship in commercial devices until 2019.

Intel characterized connectivity as an important component of a modern PC, and said that its processors have already powered 30 shipping cellular-connected PCs. “In an increasingly connected, mobile world, it’s an expectation that our PCs should be always-connected and always-on,” Intel said in a statement.

AMD chases always-connected, too

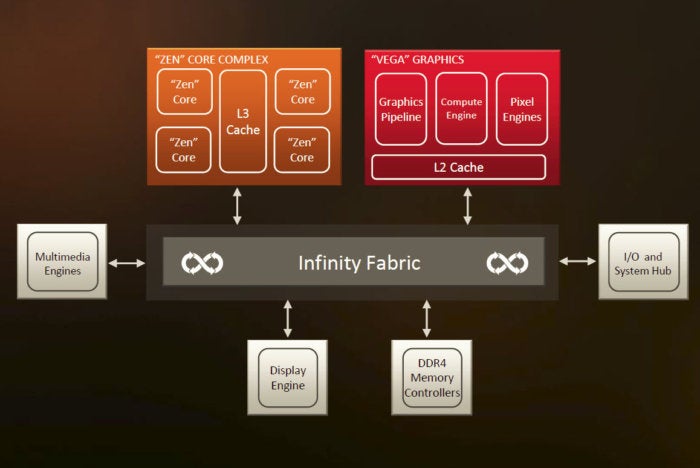

AMD

AMDThe Ryzen APU die is made up of six separate components all connected using AMD’s high-speed Infinity Fabric. In the future, there could be an off-chip connection to a Qualcomm modem.

Somewhere between Qualcomm and Intel lies AMD, a smaller company that lacks the resources to chase much beyond its core business of PC CPUs, GPUs, and sometimes server chips. Instead of pursuing its own modem, AMD tossed its hat into the ring with an announcement of a “technical partnership” between itself and Qualcomm to bring Qualcomm’s modems to its future mobile Ryzen platforms.

AMD doesn’t plan to integrate Qualcomm’s modems into its Ryzen SoCs, but operate them “alongside” its Ryzen chips, the company said. PCs using the mobile Ryzen chips —the Acer Swift 3, the HP Envy x360, and the Lenovo IdeaPad 720S, among others—are coming soon.

AMD already claims it can trounce Intel’s 8th-gen Core chips in terms of CPU and graphics performance. Supporting Qualcomm’s modems adds another advantage, said Kevin Lensing, corporate vice president and general manager of the Client Business Unit at AMD. “That high-performance processor needs a world-class connectivity solution to create the ultimate notebook,” Lensing said.

Asus via Qualcomm

Asus via QualcommThe Asus NovaGo looks like a somewhat unremarkable ultrabook, but a Snapdragon 835 chip inside helps make it something special.

The carrier question: Data costs

All this just goes to show the lengths to which chipmakers, PC builders, and an operating-system vendor will go to add a new feature. But WWAN support also ropes in an industry that usually isn’t part of the conversation: wireless carriers.

The issue isn’t really about the carrier, but about the cost. A new, always-connected PC will most likely cost $399 or so for an Intel-powered solution, and a few hundred dollars more for a Snapdragon PC. Consumers have to wonder what they’ll end up paying in terms of additional cellular fees as well. Broadband companies like Comcast have tried to strike a balance, offering up access to thousands of Wi-Fi hotspots in return for opening your own, but they’re still not as omnipresent as a cellular connection.

For now, however, the carriers’ plans mostly remain mired in the days where families would pack an additional iPad for a summer vacation, not as a daily driver. AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon all have differing approaches.

Or at least, most do. Though Sprint’s chief operating officer of technology, Günther Ottendorfer, appeared at Qualcomm’s summit, the company declined to divulge exactly how Sprint plans to address this new emerging class of devices.

“The Always Connected PC unlocks an entirely new opportunity to meet our customers’ demand for anywhere, anytime access to unlimited data, “ a company spokeswoman said in an email. “Sprint is a launch partner for these products, and is working hand-in-hand with Qualcomm, Microsoft and participating PC manufacturers to ensure customers can have a great experience on the Sprint network for this entire line of products moving forward.”

Still, she added, the company has not announced rate plans or availability. “More to come on this,” she promised.

T-Mobile is a bit clearer. As the company explains in its plan summary, subscribers who sign up for its ONE unlimited service can add an unlimited data SIM for a tablet or PC for $20 per SIM per month. “The SIM for that data line could be used in a connected computer just as it would be used in a tablet,” a company representative said via email.

Daily Caller

Daily Caller The wild card in all of this is the FCC and its chairman, Ajit Pai, which is repealing net neutrality.

For its part, AT&T charges $30 per month for 3GB of DataConnect data, according to its plan configuration page, while Verizon charges $10 per month for a gigabyte of data. Whatever your carrier, all of these costs will obviously accumulate. If you subscribe to the AT&T plan, for example, you’ll have paid as much in wireless fees as the cost of the basic NovaGo tablet in 20 months.

All this means, of course, is that some consumers will happily go back to the the free Wi-Fi in coffee shops and airports to avoid paying extra monthly fees—and who knows what will happen now that net neutrality is in the process of being repealed. Even if you can budget in the cost of a connected-PC data plan, who’s to say what will happen in six months to a year?

We’ve seen a number of initiatives emerge from the PC market in an effort to kickstart sales: tablets, convertibles, mixed reality, e-sports. Always-connected PCs appear to be next in line. On paper, they offer a compelling proposition: great battery life plus a constant connection to your data. But the real world never operates as smoothly as planned, and the road looks like it will get bumpier as always-connected PCs move closer to shipping.