Image: Microsoft

Image: Microsoft

The question rattled around the Twitterverse this week: Now that Microsoft has unexpectedly shuttered Groove Music Pass, can it be trusted to sustain other consumer products and services?

It’s not an idle question. Every cancelled consumer product—the Zune music player, Windows phones, the Microsoft Band—resurfaces the same angry protest: Doesn’t Microsoft care about consumers?

If “care” means app development, yes: Both the Zune and Groove Music Pass evolved into reasonably good services, even if few used them. If “care” refers to marketing, though, you already know the answer: In general, no. And if you follow the money—which in this case, comes mostly from Microsoft’s enterprise businesses—that’s most likely the real reason why no Microsoft consumer service can feel completely safe.

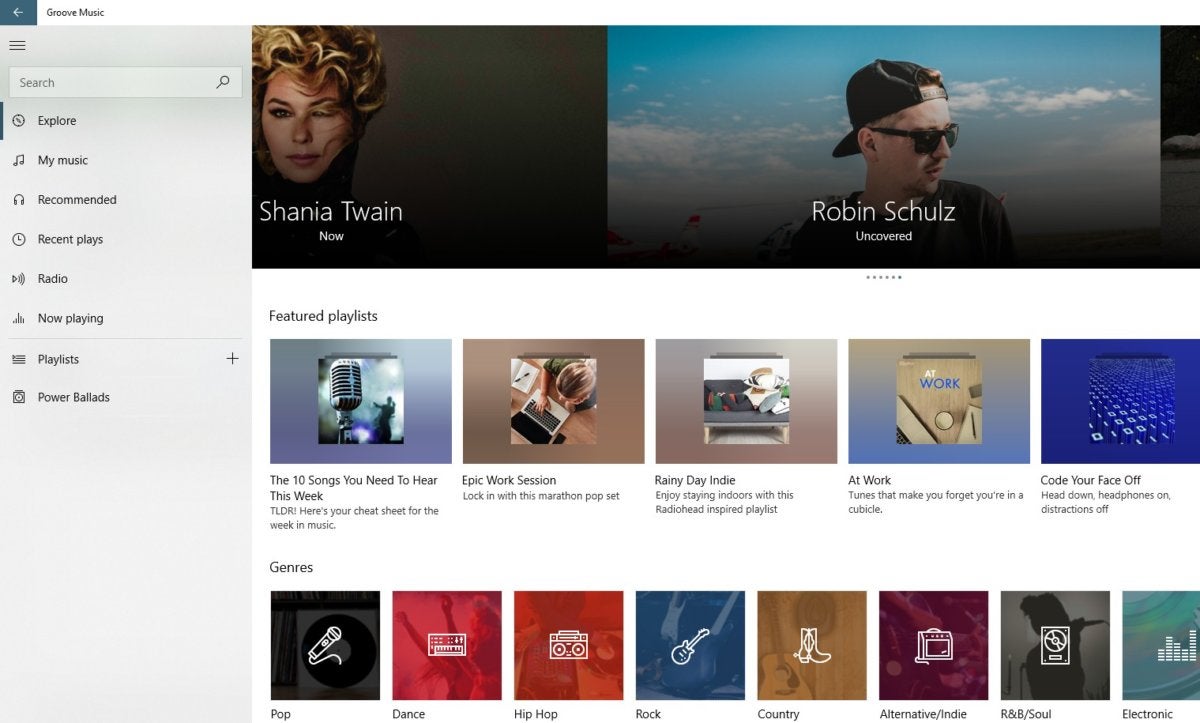

Mark Hachman / IDG

Mark Hachman / IDGThough few people used it, Groove Music Pass was a good, if not great music service, with recommendations and downloadable music. But who knew about it?

When push comes to shove, enterprise wins out

While Microsoft’s first love may have been consumers, its attention quickly turned to businesses. Windows lost its explicit consumer focus after Windows XP, and like two other tentpole products, Skype and OneDrive, it evolved to serve both consumers and businesses. Windows phones—what’s left of them—evolved from consumer products into productivity devices. And Microsoft often ignored consumer marketing—even as Apple took aim at Windows’ hegemony, again and again.

Today, Microsoft sells more to businesses and enterprises than it does to consumers. The emphasis today is on subscriptions and abstract services, rather than on shrinkwrapped products it can put on store shelves. Its watchwords are Microsoft 365, Azure, artificial intelligence and bots, not PCs and phones. So-called “consumer” devices like the Surface are really aimed toward business customers, exceptions like the Surface Laptop nothwithstanding. Still, PC executives questioned Microsoft’s commitment to the Surface line during a business event this week in Venice, Italy.

James Niccolai / IDG

James Niccolai / IDGDid Microsoft’s Band 2, shown here on display in 2016, die because of Microsoft’s lack of marketing, or just a general decline in fitness bands? Either way, it hasn’t been replaced.

When Microsoft does address consumers, though, the company at times seems almost bipolar, manically throwing 100 albums at consumers for free, than lapsing into a funk where a flagship app is hardly updated for months. For every affordably priced Surface Laptop, a Microsoft Band or Windows phone disappears. Microsoft Stores used to be showcases for the Surface, Windows Phone, and Xbox. Today, filled mostly with partner devices, they’re more like a smaller version of Best Buy. Would anyone be truly surprised if Microsoft Stores were the next to go?

If you’re a Microsoft movies customer, think again

All this has to make you wonder which approach Microsoft will take with its other products and services. We can probably safely agree that “tentpole” products, like Windows, Skype and OneDrive, serve enough business customers that Microsoft will leave them intact.

Groove Music subscribers may enjoy a smooth transition to Spotify, but it’s unclear whether other services would have it as easy. Purchased MP3 files, even albums, take up relatively tiny amounts of storage space, and Microsoft’s plan to transfer them to Spotify was well thought-out. But how much music have consumers bought from Microsoft? Those hundred albums? More? The vast majority of customers probably never bought more than a few gigabytes’ worth.

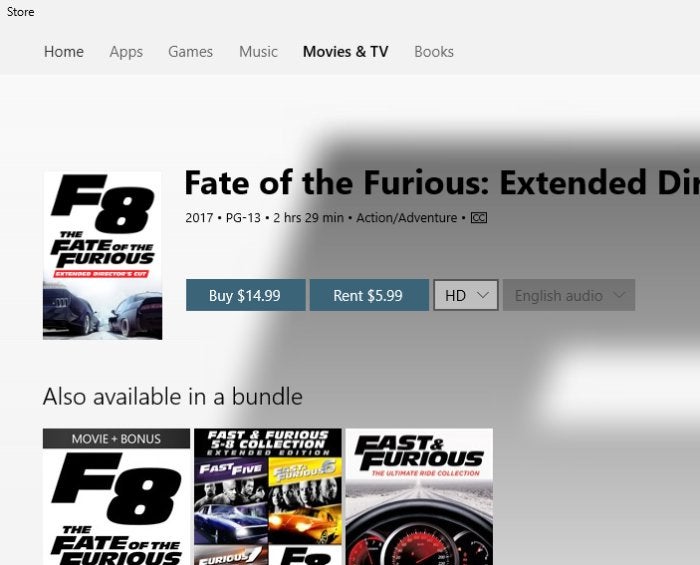

Microsoft

MicrosoftMicrosoft still has yet to offer 4K movie content within the Windows Store.

If you subscribe to Microsoft’s Movies service, though, the storage space and bandwidth costs begin to add up. HD movies clock in at 3GB to 4GB, and a bundle of all six Pirates of the Caribbean movies can run 25GB. That may be nothing compared to the size of the average online Xbox game, but the average Movies consumer would be in a jam if the service went under.

For now, everything we’ve heard out of Redmond indicates that movies, TV, and ebook sales will remain intact and will continue to be sold to customers. As of January 1, however, Microsoft’s Music tab will disappear from the Windows Store app, leaving just Apps, Games, Movies/TV, and Books. The absence will be noticeable, and consumers will wonder: What’s next?

Forking the customer: Xbox or mixed reality?

If you’re rooting for Microsoft to increase its engagement with consumers, you can’t be happy with the scenario that will play out this fall: In a sense, Microsoft will ask its customers to decide between first-generation mixed-reality hardware such as a $499 Samsung Odyssey head-mounted display, or a comparably priced $499 Xbox One X.

On one hand, you have the most powerful game console in existence. On the other, there’s mixed reality, with headsets for those who either couldn’t afford an HTC Vive or Oculus Rift or who chose to wait. Windows mixed reality devices will offer SteamVR games, including Superhot, Space Pirate Trainer, Arizona Sunshine, and more. And they’ll obviously run Windows apps. But it is completely insane to think that the untapped market for mixed reality is large enough to support not one, not two, but five different hardware partners and their individual devices.

Microsoft

MicrosoftSamsung’s Odyssey Windows mixed reality device goes up against the Xbox One X this fall, for the same $499 price tag.

It’s too early to know whether any one HMD maker will make enough off the first generation of devices to invest in a second—or blink and bow out. But everyone potentially stands to lose. If partner investment is wasted, support fizzles; then consumers feel cheated. Meanwhile, someone at Microsoft could conclude that consumer products aren’t worth the effort, save for the Xbox.

Microsoft’s relationship with consumers arguably reached its zenith about 2015, when Microsoft co-developed Windows 10 with its fans as part of a multi-device strategy that included Surface tablets, third-party PCs, the HoloLens, a hopeful future for Windows phones, and more. Since then, Microsoft’s reputation has come back down to earth: Windows phones essentially died, the HoloLens disappeared, promised Windows features were delayed or cancelled, and services like Groove are ending.

Thinkstock/Microsoft

Thinkstock/MicrosoftRight now, this is the future of Microsoft, not you.

I don’t think that Microsoft’s loyal fans want to give up on Microsoft, any more than its consumer businesses enjoy shuttering the products and services they provide. Underappreciated perks like Microsoft Rewards, Xbox Live Gold, Xbox Games with Gold, Forza Motorsport 6: Apex and the free, periodic upgrades to Windows all reflect Microsoft’s existing commitment to the consumer.

But Microsoft’s inexorable move toward the enterprise leaves its consumer businesses vulnerable, with the exception of the Xbox. And as its customers wake up to that reality, it’s hard to see how the situation will improve.