Image: Gordon Mah Ung

Image: Gordon Mah Ung

Intel’s Kaby Lake, the company’s 7th-generation Core microprocessor, was never meant to be.

Broadwell, then Skylake: Intel’s tick-tock model was supposed to move on from there to the 10-nm Cannon Lake microprocessor next on Intel’s roadmap. Struggles with 10-nm development forced Intel into its new Kaby Lake processor, however, which officially launched Tuesday.

Intel

IntelThe “7th Gen” designation is now part of Intel’s official branding.

Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that its benefits are somewhat milder than in generations past. There’s a mere 12- to 19-percent bump in integer performance, helped by a more responsive “turbo boost” capability. A dedicated, advanced video engine promises some real gains—a whopping 2.6X increase in overall battery life when playing back 4K video using specific codecs.

Otherwise, what makes Kaby Lake attractive is its familiarity: Manufacturing it should go smoothly and reliably, analysts say, and over a hundred PC designs are lined up for launch.

There’s only one problem with Kaby Lake: Microsoft says it can only run Windows 10.

At its recent Intel Developer Forum, Intel said it had begun shipping Kaby Lake. The first 2-in-1 PCs and ultrathin laptops will appear this fall, company executives said at a recent briefing. For now, Intel has made a small selection of Kaby Lake chips public: the Y-series (4.5-watt parts) for the lowest-power devices, and the more powerful 15-watt U-series chip. All include two processor cores and four threads.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngIntel’s 7th-gen Kaby Lake is built on a 14-nm process similar to that of Skylake CPUs, but manufacturing tweaks give it a performance boost, the company says.

Why this matters: Intel’s new processors typically usher in a new generation of PCs, as their makers pray consumers will rush out to buy new hardware. Kaby Lake, seems optimized for what consumers are actually doing, rather than trying to create a new market (VR, anyone?). But there’s another factor to consider: AMD’s Zen, a rival processor architecture that has promised to rival Intel’s performance. Perhaps by next summer, consumers will have some true choice in their next PC.

Kaby Lake’s modest boost in performance

For years, Intel has operated on a “tick-tock” strategy, first migrating an existing design to a finer, more efficient manufacturing process (tick), then rearchitecting the chip with new features and optimizations (tock). Kaby Lake interrupts the process, acting as a second tock after Skylake. Intel was challenged to give Kaby Lake room to improve upon its predecessor.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngIntel demonstrated an XPS 13 outfitted with the 7th-gen Kaby Lake CPU, running the game Overwatch at 720p resolution and medium settings. We saw frame rates in the 30-fps range.

The answer was a tweaked manufacturing process. What Intel calls its “14-nm+” architecture includes the same instructions-per-clock pipeline as the Skylake generation, according to Intel executives. Still, the improvements in the manufacturing process—taller “fins” in Intel’s FinFET process and a wider gate pitch, among others—boosted performance 12 percent at the transistor level and pushed up clock speeds about 400MHz overall, Intel executives said. As a result, the battery life of a Kaby Lake notebook should be up to 9.5 hours while continuously looping video.

Intel

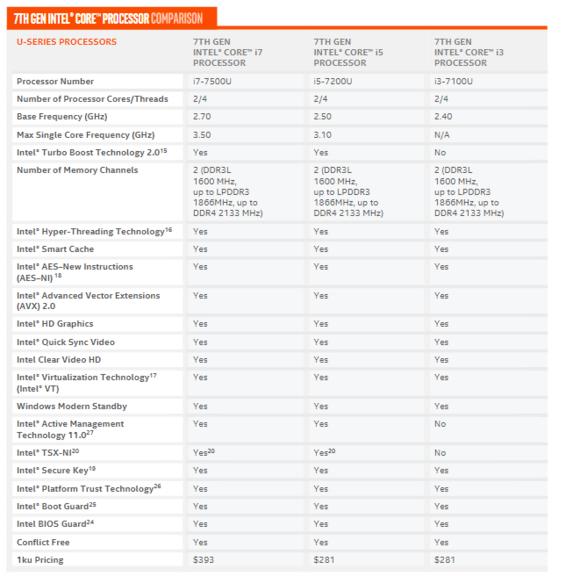

IntelA feature summary of some of the new Intel Kaby Lake U-series chips.

Within the Y-series chips, core clock speeds will span 1.0GHz to 1.3GHz, using Intel’s “turbo boost” to overclock from 2.6GHz to 3.6GHz when needed. For example, a Core i7-7Y75 Kaby Lake part will include 2 cores/4 threads, with a base frequency of 1.3GHz and a “turbo boost” frequency of a whopping 3.6GHz.

The more powerful U series, meanwhile, will run at core clock speeds from 2.4GHz to 2.7GHz, with “turbo boost” speeds of 3.1GHz to 3.5GHz. Though you’ll probably never buy either chip yourself, Intel’s public pricing on both series is identical, ranging from $281 to $393.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngIntel’s 7th gen Kaby Lake is built on the same 14nm process but improvements in manufacturing and under the hood tweaks have lead to not insignificant performance boosts depending on the task.

Be aware, however, of the important branding difference between the two processor families launched. A generation ago, the Y-series was known as Core m. Now, however, Intel has largely done away with that specific brand, dubbing it just another Core i7 instead. Only the m3-7Y30 will be officially known as a Core m3.

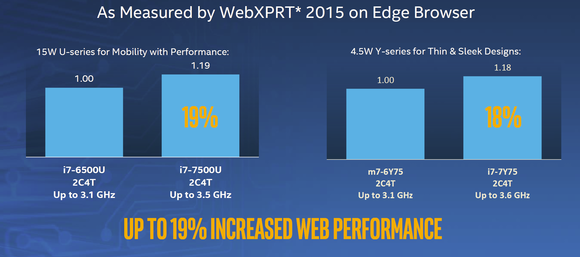

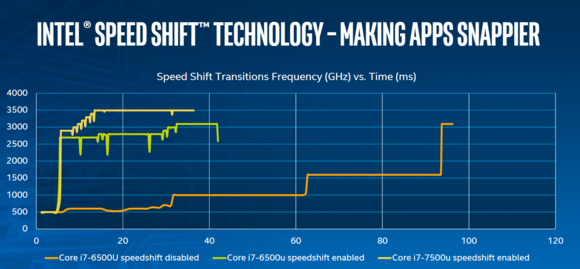

One of the elements that helped Kaby Lake’s performance is an improved “Speed Shift” technology. Intel’s “Turbo Boost” technology kicks a single processor core into an overclocked state. But Speed Shift governs how quickly that happens—and Kaby Lake accomplishes that task faster than Skylake does. That makes Kaby Lake more responsive: about 19 percent quicker on browsing with Edge—a “feels faster” improvement, Intel executives said.

Intel didn’t say anything about Kaby Lake’s graphics performance, though we’d guess (as indicated above) that it can at least play Overwatch, a popular online shooter, at decent settings. Otherwise, Intel executives encouraged reporters to compare Kaby Lake to a five-year-old PC: Kaby Lake can convert an hour-long 4K video in 12 minutes, 6.8 times faster than an ancient Core i5-2467M Sandy Bridge chip. According to Intel, it’s “three times better” in Overwatch as well.

INTEL

INTELWith Kaby Lake, the processor jumps up into an overclocked state faster than Skylake.

Otherwise, the differences lie mainly in the platform capabilities. Intel says convertible PCs and clamshells can now be manufactured thinner than 10mm, and more than 120 Kaby Lake PCs will include a Thunderbolt connection, which the chip supports.

Intel defines premium and baseline Kaby Lake configurations. The baseline spec supports up to eight USB 2.0 ports, up to four USB 3.0 ports, and up to 10 lanes of older Gen-2 PCI Express. Intel’s premium ultrabook spec supports up to six USB 2.0 and USB 3.0 ports, plus up to 10 Gen-3 lanes of PCI Express. The premium configuration also supports Smart Response Technology; the baseline does not.

Kaby Lake’s new video block makes real-world sense

The other important aspect of Kaby Lake is Intel’s transition to a new video engine. According to Chris Walker, the general manager for mobile client platforms at Intel, the web’s content platforms are moving to HEVC and VP9 for video encoding and decoding—and at higher resolutions. Skylake accelerated 1080p HEVC encoding and decoding natively in hardware, but it lacked dedicated support for 4K HEVC encoding/decoding at 10-bit depths, or VP9 decoding—two things that Kaby Lake does natively in hardware.

These advances are important for the same reason that Netflix and Google have led the way toward using both codecs: They provide equivalent video quality at a fraction of the bandwidth, especially as 4K video becomes more widespread. On Monday, for example, Netflix performed an in-depth technical examination of three of the most popular video codecs. Netflix found that HEVC delivers all of the video quality of the older AVC codec that Skylake supported, but at 50 percent of the bandwidth.

That means the amount of data your bandwidth cap chews up on account of video streaming could be half of what it is now, without a noticeable change in quality—but it would require significantly more computational horsepower from your PC. What Kaby Lake promises is that the new dedicated video block won’t actually impede your PC’s performance.

That translates into two advantages, according to Intel: first, a tangible improvement in video decoding and encoding. Naturally, a Kaby Lake system will be able to decode 4K video at 60 frames per second—or up to eight 4K streams at 30 fps.But even the ultra-low-power Y-series will be able to encode 4K video at 30 frames per second, Intel said.

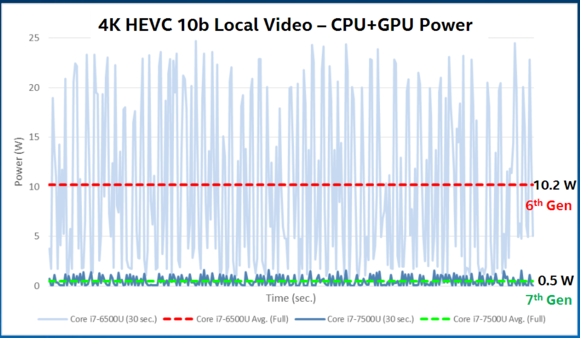

Intel

IntelThis graphic compares the amount of power used by Skylake’s CPU and graphics engine to render 4K/10-bit HEVC video, versus Kaby Lake. Kaby Lake requires 0.5 watts on average, while Skylake required 10.2 watts—an enormous difference.

Otherwise, simply playing back video will consume far less power than before. Intel claims that the power consumed by the CPU and GPU combined will be up to 20 times less than in Skylake, resulting in a whopping 2.6 times more battery life when playing back HEVC 10-bit video on a notebook with a 4K panel. Streaming VP9 video on YouTube will see smaller, but still-impressive gains: a 1.75X improvement in battery life.

It was a smart decision for Intel, analyst Dean McCarron of Mercury Research said. “We’ve got a lot of transistors to spend on processor cores,” he said. “You can squeeze more transistors into more cores or higher clock rates, or you can choose specialization, as Intel did here. Video is a really common task, with common algorithms, and it’s a good way to spend those transistors.”

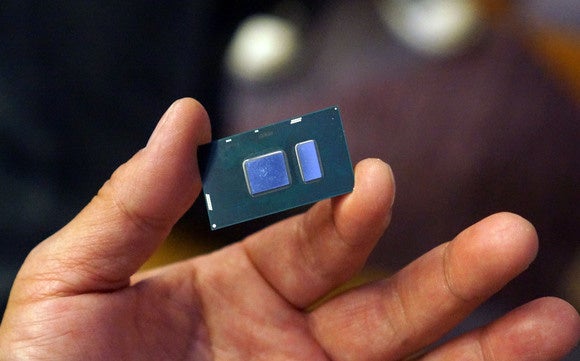

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngThis is Intel’s new 7th-gen Kaby Lake CPU, which will initially come in a dual-core variant.

In January, expect to see additional products for enthusiast notebooks and desktops, as well as workstations and servers for the enterprise, Intel executives said. They’ll include new “Extreme Edition” chips, 65-watt S-series chips, and quad-core H-series chips.

For now, though, Intel and the PC industry merely hope you’ll find Kaby Lake worth buying. For years, Intel has tried to direct the PC industry—you might recall its fixation with ultrabooks and two-in-one tablets. Now, it’s more responsive to what customers are actually doing with its products. Intel’s stance might have been different had it developed a potent mobile processor that it could turn to as PC sales fell. Until it can make its embedded future a reality, though, Intel still needs your business.

Additional reporting by Gordon Mah Ung.