Image:

Image:

As with any big piece of software, Linux is complex, and difficult for outsiders to comprehend. That’s why it’s not terribly shocking that a 9-year-old Linux kernal vulnerability, known as Dirty COW, wasn’t patched until just a few days ago on October 20.

First off, here’s a quick reminder of what Linux is: Linux is a kernel, just one piece of software in the GNU/Linux OS, with the GNU suite of tools making up the majority of the base operating system. That said, the kernel is one of the keys to the OS, allowing the software to interact with hardware. Linux’s importance to servers and infrastructure means that a lot of eyes are constantly looking at the kernel. Some of those eyes belong to employees at companies like IBM or Red Hat who are paid to work on it full-time. That’s pretty impressive for a piece of software that’s freely given away.

Still, bugs within the kernal can be overlooked. And some of them, in the right conditions, can be real doosies, as Dirty COW demonstrated.

Here are a few ways you can protect your Linux PC from future exploits.

Check your kernel and update if needed

The Dirty COW bug may have gone unresolved for nine years, but it was fixed pretty quickly after it was discovered. With only seven lines of code, the patch prompted the release of a new kernel. If you’ve upgraded your kernel since October 21, you’re most likely protected.

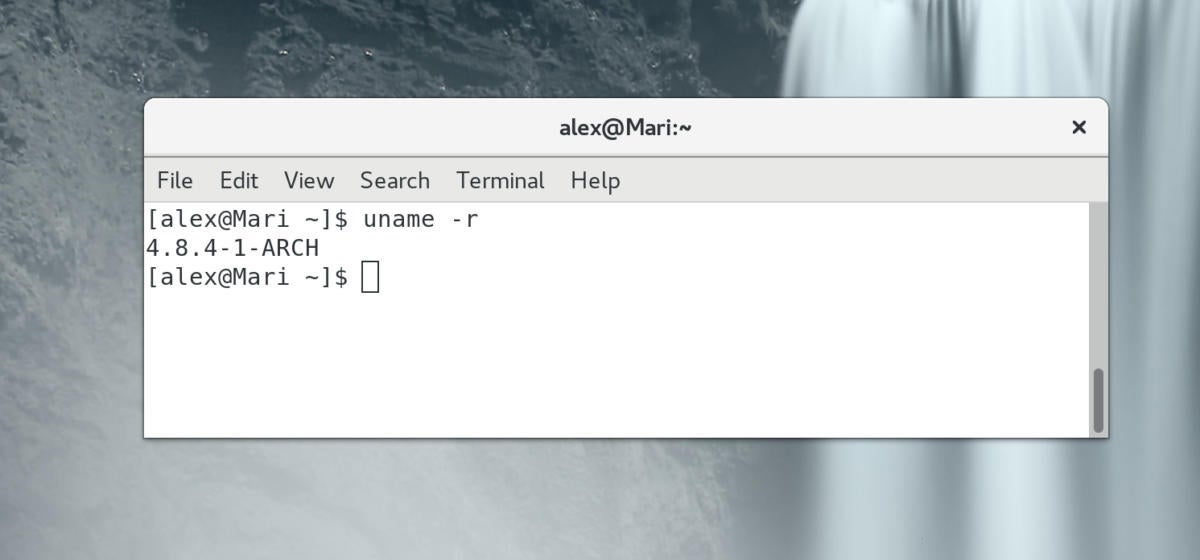

Execution of uname -r will show you what kernel is running. This PC is running kernel 4.8.4, which has the Dirty COW patch applied.

If you’re not sure what kernel you’re running, type uname -r into a terminal window. Don’t worry about trailing words like “ARCH” or “ubuntu,” since they just signify what specific distribution the kernel was built for.

The thing is, some users use different kernel versions depending on their application or preference. Make sure you have at least one of the following kernels or newer, depending on what kernel version you’re using. The older numbers refer to long-term support (LTS) versions:

4.8 (stable): 4.8.34.4 (LTS): 4.4.264.1 (LTS): 4.1.353.18 (LTS): 3.18.443.16 (LTS): 3.16.383.12 (LTS): 3.12.663.10 (LTS): 3.10.1043.2 (LTS): 3.2.83

I should note that as of this writing, kernel v3.4 has not yet had the patch applied. (The last commit was in April.)

Upgrading your kernel

Upgrading your kernel is easy enough. Ubuntu Desktop should automatically prompt you to update, especially when there are security updates pending. However, there are are a few ways to update manually, and they differ for each distribution.

Ubuntu/Ubuntu GNOME/Kubuntu/Linux Mint

The primary way to upgrade your kernel is to upgrade the system:

$ sudo apt-get update$ sudo apt-get dist-upgrade

Note that the second command isn’t apt-get upgrade like you might use to update other packages. Ubuntu does not upgrade kernel packages with that command.

Red Hat/Fedora/CentOS

To upgrade the kernel, you simply need to use yum:

$ sudo yum -y update kernel

Alternatively, you can update the system using yum as well:

$ sudo yum update

Arch/Manjaro

Updating your kernel with arch is a piece of cake with pacman:

$ sudo pacman -Sy linux linux-firmware

You can also accomplish this with a full system update:

$ sudo pacman -Syu

Once you’re done updating your kernel, reboot and run uname -r to verify that you’re running the updated version.

A little more on updates

As with any OS, installing updates regularly helps make sure vulnerabilities are mitigated. One of the great things about Linux is that it won’t apply updates unless you tell it to. (You can create scripts and cron tasks to apply updates automatically, but those scripts and cron jobs have to be created by the user.)

If you want to be reminded of when you should update yourkernel and can’t or don’t want to let your OS remind you, you can use asimple IFTTT recipe, like this one I created. Kernel.org publishes an RSS feed that gets updated every time a new kernel is released. The feed is for all kernels, so besure to search for your version.

The bad side to this approach is devices running unpatched Linux kernels can be all over the place. There’s a good chance your router is running Linux. Unless you’re using something like DD-WRT, you might have to wait a while for updates, if you get them at all. Connected devices like thermostats are much harder for the user to update, as well. For those devices, you pretty much have to rely on the manufacturer to deliver patched software.