Image: Gordon Mah Ung

Image: Gordon Mah Ung

Updated with two new USB-C laptops that support Power Delivery.

Interested in USB-C chargers and charging? Here’s the sequel to this story that shows the world has indeed changed.

We’re here to tell you about the second way USB-C is great for technology. You already know the first way—the ability to plug a cable into your device without thinking about the orientation. Hallelujah. But the overlooked advantage—for laptops, at least—could be the promise of universal USB-C charging. Rather than always having to carry your laptop’s charging brick with you, you could, in theory, just borrow a friend’s charger.

Technically, charging over USB can occur over USB Type-A ports too, but most vendors I’ve talked don’t think that’ll be adopted. Instead USB-C seems to be the port everyone is coalescing around.

Today, of course, we’re a world away from that reality. From Microsoft’s Surface Pro 4 to Apple’s MacBook Air 13, the vast majority of laptops still use proprietary chargers. Still, a few USB-C-powered devices do exist, and we gathered them up to stage a “plugfest,” testing USB-C’s potential for universality.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngAll three of these laptops have USB-C ports for charging, but does that mean their chargers are interchangeable? Let’s find out!

Our USB-C-powered subjects included Apple’s MacBook 12, Google’s new (2015-era) Chromebook Pixel, HP’s Spectre X2, and the Huawei-built Nexus 6P smartphone. We’ve also since added Dell’s newest XPS 13 and Razer’s Blade Stealth. All feature the newfangled USB-C port, and all but the Dell comes with its own charger. Dell, cleverly, can be charged via a standard Dell plug or its USB-C port.

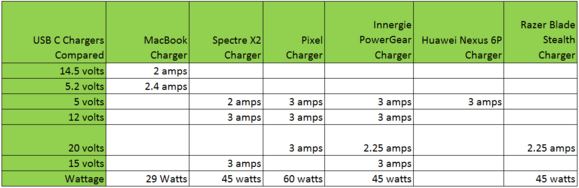

I also threw in a curve ball by including Innergie’s new PowerGear USB-C 45 charger. As its name implies, it has a maximum output of 45 watts, and is certified to work with Apple’s MacBook.

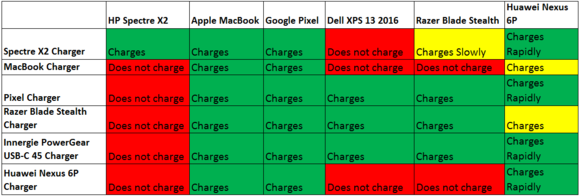

For the first test, I took each device’s charger and plugged it into another device and noted whether it would charge from within the OS. If I’d taken another week or so to play, I could have drained the devices and measured the time it takes to recharge. At this stage in the game, however, I’m most concerned that a device charges—period.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngOn top is Apple MacBook 12 followed by: Razer Blade Stealth, HP Spectre X2, Dell XPS 13 2016, Google Pixel 2015. All charge via USB Type-C ports using Power Delivery.

When I think of universal laptop charging, I think of the famous World War II photo of Soviet troops shaking hands with American troops on the shattered Elbe River bridge. Do the results of my tests live up to this symbol of unity and signify an end to proprietary bricks? Not quite.

When I originally did this plugfest, I had just three laptops that charged over USB-C ports: The HP Spectre X2, Apple’s MacBook 12 and Google’s Chromebook Pixel. For the most part, it worked as you expected: Google and Apple’s bricks worked with each other and both also charged from HP’s charger. HP was the odd-duck device—more on that later.

Where it gets more complicated is with Razer’s new Blade Stealth and Dell’s updated XPS 13. Both worked just fine with the Pixel and Innergie, but they had issues with the HP and Apple chargers. Here’s the nitty-gritty with green as a go, and red as a no-go.

We’ve tested two more laptops for Power Delivery over USB Type-C and here’s how they do.

Things are hunky-dory for Apple and Google, but the actual PC OEMs are little more picky about their charging habits. Why is not clear to me, but it could be which power rails they charge from and what the chargers provide. It’s no surprise, for example, that the puny Apple charger can’t charge the higher-powered Dell and Razer laptops. I suspect it would work with the HP device if HP let it.

Some good news, some bad news

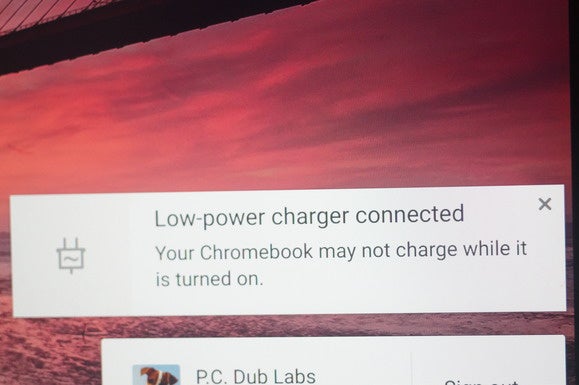

One fantasy I’ve had is charging a laptop using a smartphone charger. That reality isn’t quite here yet. I could actually charge the MacBook 12 with its tiny screen and Core m chip with the tiny 15-watt Nexus 6P wall wart, but it did so only at a much slower rate. The Chromebook Pixel also accepted the phone’s charger, though it flashed an alert about a “Low-power charger” and warned that the laptop may not charge when powered up. I doubt you’d be able to charge any laptop that’s under a heavy power load, but in a pinch, a USB-C phone charger could do the trick. Think about that: You could probably just borrow your friend’s smartphone charger when your laptop battery dies!

The same phone charger couldn’t get along with the bigger, hungrier devices. The XPS 13 was a no-go as well as the Razer Blade Stealth—even when off. The Spectre X2 also didn’t work but that was no surprise (see below.)

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngPlug a smartphone charger into the new Google Pixel’s USB-C port and it’ll warn you that the device may not charge when on.

Why HP’s the odd duck

In the chart above you can see there’s one vendor with a glaring-red problem: HP with its Spectre X2. Keep in mind, I’ve updated the Spectre X2 with the latest UEFI and it still won’t work with third-party chargers. Here’s why.

After speaking with HP officials about the issue, it appears the company is just playing it safe. Fearing that a counterfeit or out-of-spec charger could make the touchscreen or audio subsystem flaky, HP has limited the access non-certified chargers have to the device. For now, HP exec Mike Nash told us, only “overnight” charging, or charging while the device is off, is supported.

”Are we being too conservative?” Nash asked. “I don’t think so.”

HP is committed to USB-C—it already has four or five devices that use it for charging. The company just doesn’t believe the spec is ready for interchangeability yet.

Lee Atkinson, a distinguished technologist at HP who’s been leading the effort to corral PC makers around USB-C, said the upcoming Power Delivery 3.0 spec should solve many of the outstanding issues, such as how much voltage to supply and how to control which way power flows between two devices. Atkinson said OEMs all agree it has to be done correctly and with group consensus.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngWe push harder on USB-C charging

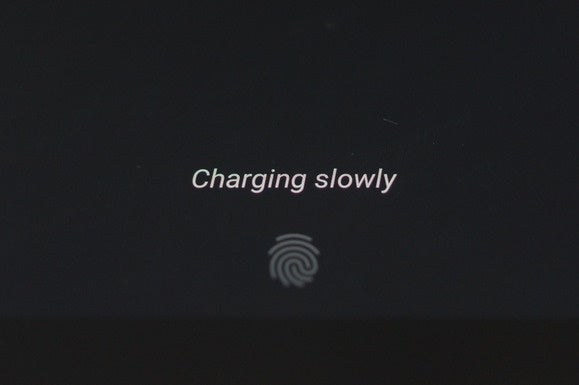

With the laptops taken care of, we took a closer look at the Nexus 6P, plugging it into each of the laptops using the stock USB-C cable to see what would happen. (The laptops were powered on and running on battery.) In all cases, the phone charged, but as we discovered with the power bricks, the Nexus 6P’s charge rate varied. On the Spectre X2 and the MacBook 12, the Nexus 6P charged at its presumably higher “Charging rapidly” rate. On the Google Chromebook Pixel, however, the Nexus 6P reported “Charging slowly,” which suggests a step down from just “Charging.”

Oddly, when plugged into Google’s new Pixel over a standard USB-C cable, the Google Nexus 6P charged at its slowest rate.

The discrepancies between the Nexus 6P’s charging rate with the power bricks versus the standard cable is likely due to how much power the USB-C ports on the devices put out versus how much the power bricks put out. If you’re curious about the voltage and amperage of the various bricks, see the chart below.

Not all USB Type-C chargers are the same

Ever since Google’s new Chromebook Pixel came out, I’ve wondered what would happen if you plugged a separate USB-C charger into each of its USB-C ports. Like the Spectre X2, the Pixel can be charged from either port. I plugged the MacBook’s charger into the left port and the Pixel’s charger into the right port.

Nothing caught on fire (darn!), but the Pixel is smart enough that you can pull a charger from either port and it won’t skip a beat. I could, for example, unplug the Pixel charger and have it run on the MacBook charger, and then plug the Pixel charger back in and unplug the MacBook charger, without interruption.

HP mentioned that one of the issues still being worked out is how the spec responds when you connect one laptop’s USB-C port to another’s. In theory, the Power Delivery spec allows you to charge a friend’s laptop from yours, just as if you were jump-starting someone’s car.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngUSB-C’s Power Delivery mode should allow the Google Pixel to charge the Apple MacBook 12.

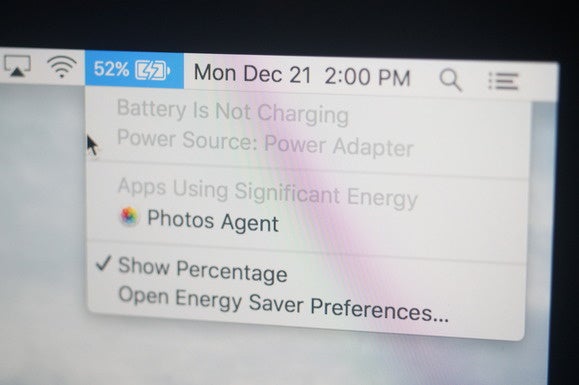

To put that to the test, I took the Google Pixel with its battery at 100 percent and plugged it into the MacBook 12 at 61 percent. The charging icon on the MacBook changed, but its battery continued to discharge, and the OS indicated that it wasn’t charging at all.

Gordon Mah Ung

Gordon Mah UngThe lightning bolt suggests that the Google Pixel is charging the MacBook 12, but the latter started out with 61 percent battery.

Conclusion

I have no doubt that universal charging for laptops will be a reality one day on laptops, but right now it’s pretty messy. Whether that’s because vendors are “waiting” for the new USB Power Delivery 3.0 spec or they still have warehouses of power bricks to purge, I don’t know.

When I started this project with three laptops, I was far more optimistic that it would “just work.” Since I’ve added two more laptops to the mix, it’s become clear to me that a lot more has to happen first.

The most embarrassing aspect for PC fans is it’s the OEMs who seem to be be in the most disagreement, while Apple, Google, and Huawei are more accepting. To be fair to PC OEMs, they make the most laptops. Apple and Google’s MacBook 12 and Pixel units moved probably don’t add up to 1 percent of what Dell and HP ship in a month, so there’s simply less interoperability to worry about.