As crucial as the ocean is to countless industries, we lack the kind of systematic knowledge of it that we have of the surface. Syrenna has built a versatile robotic platform that you might think of as a mobile weather station for the sea, and is ready to emerge from stealth to enable precise, real-time monitoring of Earth’s largest liquid asset.

It may surprise you how little we know about the ocean. Certainly we know a lot in general, trends and patterns over seasons and decades. But when it comes to specifics, like what is the temperature, salinity and microplastic count two miles off the coast of Barcelona at 20 meters deep right now, we’re clueless.

This is partly due to the simple fact that the ocean is gigantic and there’s simply no way (or need) to monitor all of it. But even areas important to fishing, oil and gas, tourism and other maritime industries are checked by labor-intensive or expensive methods like sending out a ship or robotic underwater vehicle. Cheap solutions like buoys are great but limited to surface measurements, and are subject to the whims of weather and currents.

Syrenna’s solution distills several methods into one: a robot that can control its own depth while maintaining geographic location, allowing for persistent, near-real time sensing and tracking of any number of important marine metrics.

“There is such a clear need for safe, reliable and continuously updated data about water quality,” said Ester Strommen, CEO and co-founder of Syrenna. “Widespread use of technology will drastically increase our knowledge of how our oceans are actually doing; we could detect harmful bacteria, runoff and pollution, track global warming, monitor species and conduct subsea surveillance.”

Cerulean empowers ocean pollution watchdogs with orbital observation

In case that last use case rings alarm bells, think more along the lines of catching illegal fishing than invading your privacy. The lack of real-time marine intelligence leads to illegal activities at sea, like dumping and poaching, which we can only now estimate the scale of using satellite imagery.

Free-floating, free-diving

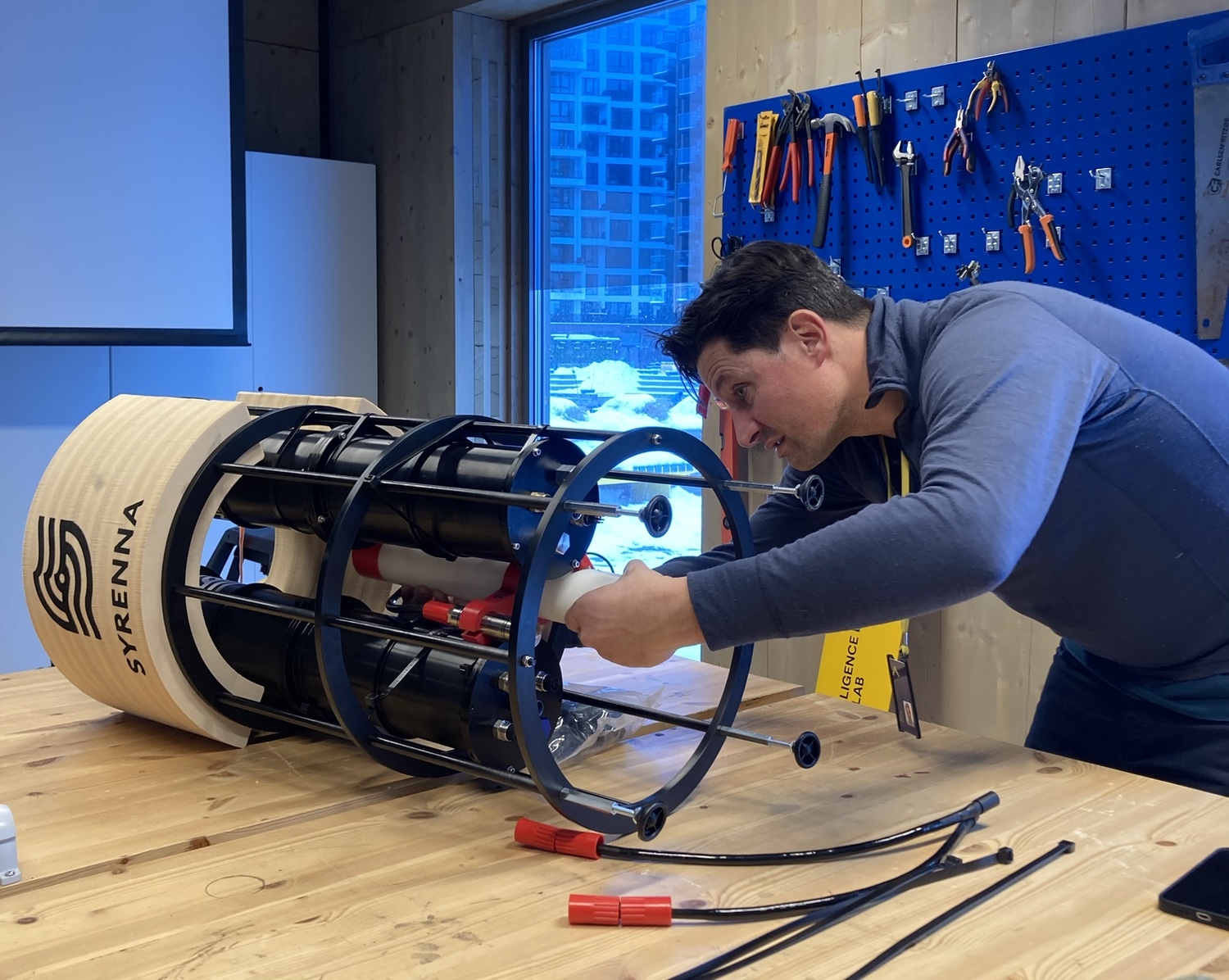

I saw a prototype of the WaterDrone, as they call it, while visiting startups last spring in Oslo, where Syrenna is based. The robot is based on the research of Alex Alcocer, who hooked up with the other founders through early-stage investor Antler’s incubator program. (Parts of the robot are licensed from Oslo Metropolitan University’s OceanLab, where Alcocer first developed them.)

It’s totally sealed against the water, except for the sensors that must sample or observe it, and incorporates a sort of swim bladder that allows it to rise and fall to any depth. Meanwhile, a proprietary tether keeps it anchored near its target location even in rough seas — which, for that matter, it could simply sink the bottom to avoid. The whole thing is powered by a battery that lasts for a full year of operation, and the team is working on having it recharge when it comes to the surface and transmits its latest data (via Iridium’s satellite network).

Since I visited and saw the WaterDrone (about the size of a bedside table) in its little tank, Syrenna has finished up the next version of the hardware and taken it out for a real-world pilot in Oslofjord, working with Norwegian marine research organizations NIVA and IMR. They conducted a second test bringing the drone down to 180 meters in an offshore location west of the country, and long-term tests in the wild are also underway.

A few of these bots lurking in territorial or leased waters could provide a stream of data of reliable value to energy company interests, from oil and gas to wind and thermal power. Governments are also interested, for basic research and awareness purposes, as well as law enforcement and military reasons.

The final cost of the robot is not set yet, but Strommen was clear that it’s a fraction of the cost of autonomous surface or underwater vehicles and the crewed ships that have to deploy and maintain them. Think on the order of hundreds of thousands for years of active deployment. At that price, it’s not wild to think of countries buying a few dozen or a hundred WaterDrones to scatter around their ports and other aquatic areas of interest.

The business model is refreshingly straightforward: people buy the robots. Though there will probably be some more complex arrangements, this is what customers are used to today, Strommen said. No need for an elaborate leasing or joint-ownership scheme when the clients have cash in hand and are ready to slap it on the counter.

The company also hopes to open up data to the public that has been collected on the private dime — tracking ocean temperatures, pollution and other trends at such a granular level is something many researchers would love to do, and it’s no use stashed in some energy company’s private database. So they plan to work with Hub Ocean and other organizations to collect and release metrics important to science and the public interest.

Syrenna has been operating in bare-bones mode since it was founded in 2022, and focused first on executing the hardware, meaning their work and hiring has been engineering-centric. Now that the company is actually going to sea and showing its robot at work, they can focus on the important part: convincing execs to buy in.

“We are really eager to have improved visualizations and BI tool integration, so the data is not just understandable to engineers and marine biologists but also for the C-suite and general audience,” Strommen said. “To do this, we need more full-stack developers.”

Their current raise, totaling just over $1 million with both private and public investments, is aimed at getting them to that next phase. “After this, we plan to raise a substantially higher amount,” she added — presumably to kick off manufacturing.

“These funds are raised from our initial investor Antler as well as the industry-specific accelerator Katapult, angel investor Harald Norvik (former CEO of energy giant Equinor), grants from Innovation Norway, Research Council of Norway and European Space Agency Business Incubation Center Norway,” according to Strommen.

Collecting more and better information about the ocean, whether for industry, science or conservation purposes, has been the focus of a number of startups and nonprofits. Companies like Bedrock aim to map the ocean floor, while Saildrone is improving its autonomous surface vehicles and the aforementioned satellite-based monitors are also picking up — but Syrenna is unique in its ambition to provide this kind of semi-stationary weather station. Between these different modalities (and surely some to come) we may be able to form a more comprehensive — and actionable — picture of the planet’s waters.