Image: CTA

Image: CTA

The Electronic Entertainment Expo, perhaps the most over-the-top, bombastic event ever to be designated an industry trade show, is no more. E3 was a staple of the video game calendar for over two decades, showing off the latest and greatest in gaming hardware and software every summer. But it’s been officially declared dead by the ESA, in the wake of diminishing trade shows worldwide post-Covid pandemic.

E3’s demise wasn’t exactly shocking, since it hasn’t held a live, in-person event since 2019. But the closure of such a high-profile event has some people wondering: Is CES, the electronics industry’s most high-profile event, next on the chopping block? I don’t think so. Let’s explore why.

E3 outlived its usefulness

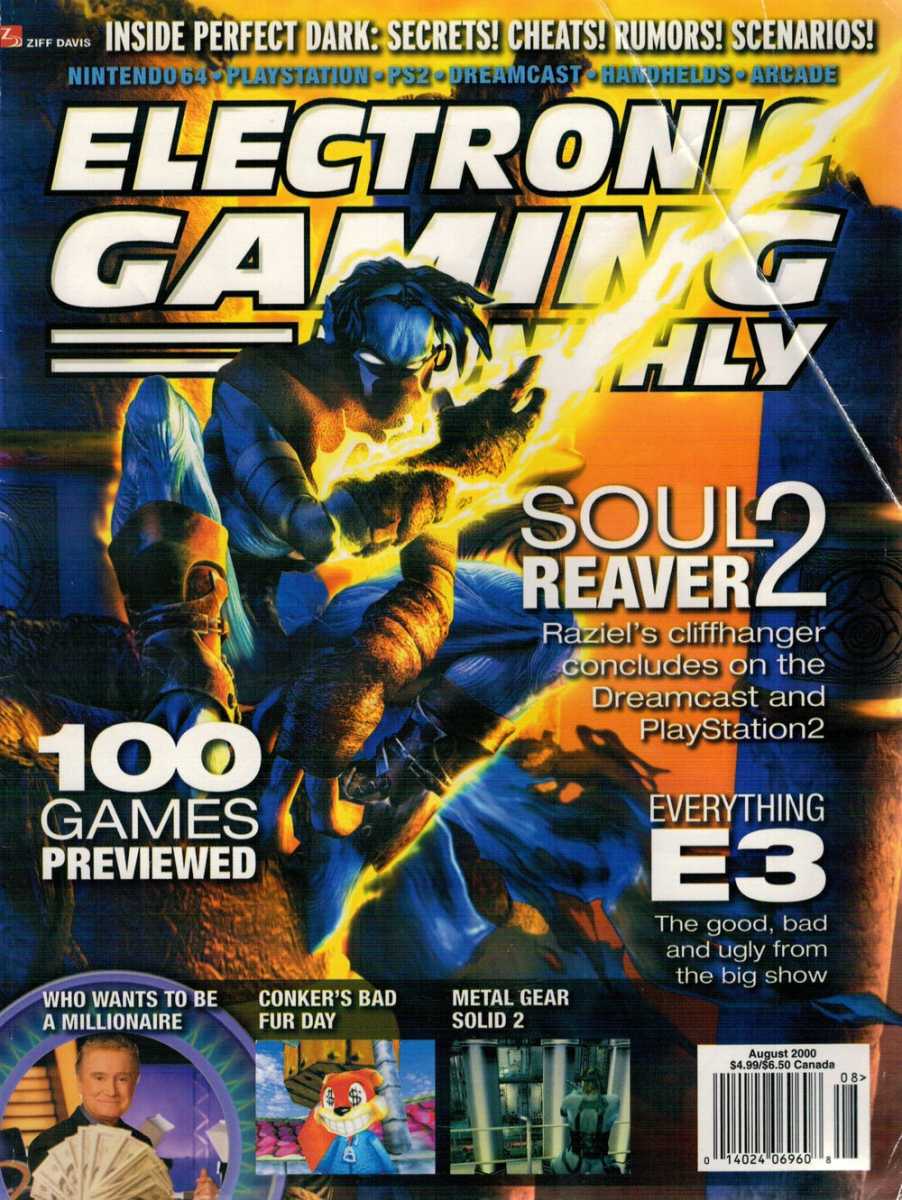

For a game industry growing by leaps and bounds in the late 90s and early 2000s, E3 was a necessary showcase for pretty much every major player. Alongside smaller regional shows like the Tokyo Game Show and Game Developer’s Conference, it was a chance for game publishers, developers, and hardware makers to take to a huge stage and show their upcoming work directly to the largest gathering of press. The press then passed along the news to gamers worldwide, through the medium of print magazines and the beginnings of online news.

E3 Expo (Electronic Entertainment Exposition) at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles, California on June 17, 2015

E3 Expo (Electronic Entertainment Exposition) at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles, California on June 17, 2015

Glenn Francis/Wikimedia

E3 Expo (Electronic Entertainment Exposition) at the Los Angeles Convention Center in Los Angeles, California on June 17, 2015

Glenn Francis/Wikimedia

Glenn Francis/Wikimedia

Herein lies the thing that a lot of people forget about E3: It was originally just an event put on by the industry, aimed at the press. Because in the 90s and 2000s, that’s how you got the attention of gamers. Budgets for direct advertising on TV and in public ads could only go so far. If you wanted to get the word out and get people excited, you had to get ink, in magazines like Electronic Gaming Monthly, GamePro, Computer Gaming World, and dozens of other targeted publications. You then doubled down on this strategy with print ads in the same mags.

If you’re my age or older, you can probably see where this was going. The rise of the web didn’t just kill the print industry and the print arm of the gaming press, it created a seismic shift in the way that games were marketed. As the game industry itself grew large enough to start advertising directly on primetime TV and even alongside Hollywood movies, web advertising allowed marketing to stretch to every facet of our lives.

Ziff Davis/Lord Aevum/Fandom

Ziff Davis/Lord Aevum/Fandom

Ziff Davis/Lord Aevum/Fandom

Suddenly gamers were getting ads for new titles alongside their social media feeds, while they were shopping for sneakers, while they were paying for bills. Before long simple animated ads gave way to full-on trailers on YouTube, directing players to custom-made promotional websites. With the rise of Steam and digital console stores, game publishers could advertise a new game, sell it, and deliver it, all without needing to involve the press in any way. It was a dream come true, unless your dream was to be a game journalist.

There’s still a gaming press, because there’s still a gaming community. But the press is no longer the town crier of the industry. It’s fallen back on its role as the buffer between the people who make games and the people who play them. You’ve probably noticed that while gaming sites and channels still cover news about announcements and releases, they’re far more focused on finding and highlighting obscure indie games, publishing reviews and editorials, and covering the kind of industry news that publishers often wish didn’t make any kind of news at all.

This shifting of the press makes a direct, centralized event like E3 less relevant. Why would a publisher spend so much time and energy, and of course, money, wooing a few thousand journalists? It’s far more efficient just to throw a trailer up on YouTube and spend that money on direct advertising. Odds are pretty good that if you’re a big enough developer, gaming news sites will still publish news stories about it, especially if your PR department gives them a few email nudges.

YouTube killed the gaming show

Don’t get me wrong, there’s still a market for a centralized display of everything publishers have to offer to gamers. But these events are now smaller, more focused, and increasingly controlled by a single company.

Nintendo’s Direct, a mini-presentation showing off whatever new Switch games the company has planned for the next few months, is a perfect example. Nintendo Direct shown, well, directly to millions of fans around the world with no need for gaming press. (Though the press still covers it anyway!) And it’s also ready to go whenever Nintendo feels like it, foregoing the need to have any particular project ready for a reveal at E3 or Space World. Gaming companies would follow in the steps of Apple a decade or so before, which still makes its own events around every big new announcement, more or less on its own timetable.

Other companies like Sony, Microsoft, and even smaller ones like Devolver Digital emulated this successful model, showing off collections of games and gadgets in online debuts, often without any kind of real-world event. Shifting from big bombastic in-person displays to more efficient and effective online advertising was already dropping E3’s relevance in the mid-2010s. By the time of the Xbox One and PS4, Microsoft and Sony were already using their own pre-show events to highlight new hardware announcements, and Sony and Nintendo had all but abandoned any large presence at the show by 2019.

E3 tried to shift to a generalized show, akin to a Comic-Con-style celebration more than an exclusive event, attempting to attract the kind of fan presence that makes shows like PAX a huge draw to this day. It even opened its doors to anyone who wanted to attend in 2017. But with the industry presence that made E3 notable in the first place diminishing steadily, the proverbial writing was on the wall.

With worldwide travel crippled in 2020, E3 “went digital.” But by this point basically every major player shifted to direct online presentations, so there was no reason to go to the ESA to deliver something that marketing departments could do on their own. The biggest event on the gaming calendar died with a whimper three years later.

What makes CES different?

Will the Consumer Electronics Show follow in E3’s foreshortened footsteps? I don’t think so. While the pandemic certainly delivered a harsh blow to CES (as a huge, international affair in January 2020, some in the tech industry wonder whether Covid played a role in the pandemic’s early spread), the crucial thing to remember is that CES isn’t just about the electronics press.

As both a member of the press and a voracious consumer of computer and electronics news, it’s easy for me to wear blinders and focus only on what affects consumers directly. That is, after all, the major focus of PCWorld, and most of its online competition. But that’s the tip of the iceberg, both for the industry as a whole and for industry events like CES in particular.

Consumer Technology Association

Consumer Technology Association

Consumer Technology Association

For every CES story you read about a cool new gadget, there are a hundred more that don’t get covered, because the show floor has so much going on that it’s literally impossible for even the biggest consumer-focused sites to see it all. And I’m not just talking the big players, with their massive booths bigger than most people’s homes.

CES is attended by literally thousands of companies showing off their latest wares, from LG and Samsung taking up more space than a car dealership to tiny international startups that might send a single person and a folding table. You could spend the entire week in Vegas just perusing the smaller, sweatier aisles, where people from all over the world gather to see everything from self-sealing stem bolts to reverse ratcheting routers.

Underneath the iceberg

And that’s just the stuff on public display. CES spreads out from the Las Vegas Convention Center to all of the massive surrounding hotels, with pockets of displays and smaller events all over the Vegas strip occurring all week. This is where companies who don’t have the budget or the manpower to market directly to consumers hope to get a few articles printed from journalists hungry for the scoop on what their competitors haven’t covered. And essentially, it’s the kind of coverage you can’t find browsing YouTube.

But even looking at these smaller and more far-flung corners of CES, and other trade shows like it, won’t show you the whole picture. Because CES isn’t an event aimed at consumers, or at least aimed exclusively at them. There’s a business-to-business side of the show that we don’t ever get to see — and by “we,” I mean both the writers and the readers of articles like this one.

Fauxels/Pexels

Fauxels/Pexels

Fauxels/Pexels

CES is where a remote control manufacturer from Taiwan can meet with a TV maker from Japan and decide that they’ll source their button membranes from a German rubber supplier. It’s where a mid-level manager from Company A might spot her former coworker from Company B and swap business cards (yes, on dead tree paper), and come back in three years after forming their own consulting firm. These and other connections are happening a thousand times a day at these shows — the kind of connections that simply can’t be replicated anywhere but in person.

Though CES stumbled during the pandemic, it’s come back into relevance far faster than any show lacking this deeper industry component. The Consumer Technology Association, which runs CES, is projecting 130,000 attendees for 2024, significantly lower than its 2017 record attendance, but still bigger than last year and the largest event in the industry by far. It’s easy to look at CES and just see indulgent floor booths and huge crowds. But the biggest decisions, the crucial parts that make it valuable as more than just a yearly megaphone, happen behind closed doors.

As long as those doors are valuable, CES and other shows like it aren’t going anywhere…barring the occasional worldwide catastrophe, of course.

Author: Michael Crider, Staff Writer

Michael is a former graphic designer who’s been building and tweaking desktop computers for longer than he cares to admit. His interests include folk music, football, science fiction, and salsa verde, in no particular order.

Recent stories by Michael Crider:

Comcast backs down on misleading ’10G’ Xfinity speed labelMicrosoft owes $29 billion in back taxes, IRS saysThe FCC wants broadband internet speeds to quadruple