On the shelves of a laboratory near San Francisco sit tanks and tanks of mysterious-looking liquids. Labels identify some as simulations of human heads, while others relate to muscles.

It sounds like the ghoulish headquarters of a mad scientist, but it isn’t. It’s the Silicon Valley offices of UL, a product testing organization previously known as Underwriters Laboratory, and these liquids play an important part in smartphone safety.

You might not know UL, but you can probably find its logo on a number of products around your home.

Martyn Williams

Martyn WilliamsTwo UL logos are seen on a computer power supply. The company tests products to ensure they meet safety requirements.

Manufacturers contract with the company to run tests and ensure products meet safety and regulatory guidelines. This laboratory is used to test for electromagnetic radiation coming from phones.

Electromagnetic radiation is emitted by all electronic devices. You’ll sometimes experience it as interference on a radio or television, and in the context of smartphones, there are legal limits on how much RF (radio frequency) radiation they can emit. The standard is how much a human body can safely absorb.

That standard is based on the specific absorption rate, or SAR, and that’s where the liquids come in.

Martyn Williams

Martyn WilliamsContainers of liquid designed to simulate the human body sit on shelves at UL in Fremont, California, on April 13, 2017.

“The liquid is designed to emulate the electric properties of the human body,” said Dave Weaver, program manager of the SAR lab. There are different liquids that simulate tissues in muscles and the head.

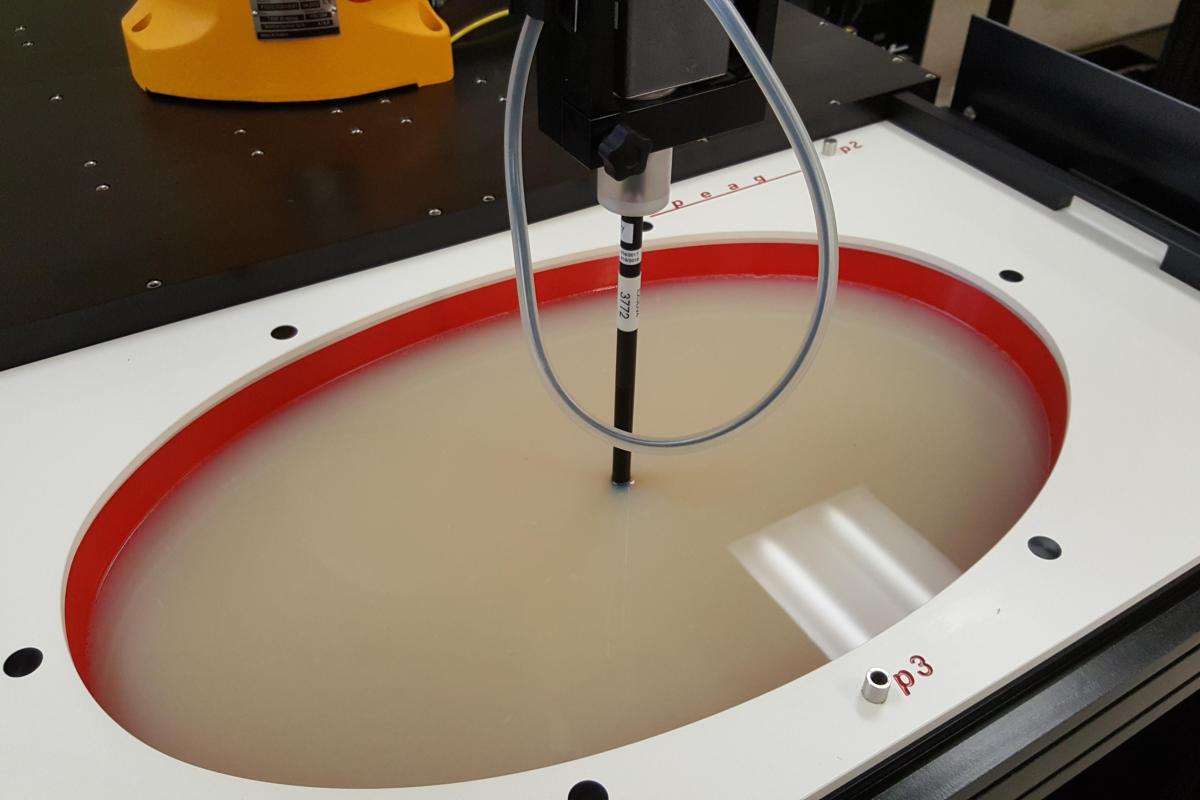

His lab has four testing stations that each sit above a different mold, some to simulate the head and others to simulate the torso. The liquids are poured into their respective molds and a cellphone is placed underneath, and with a whirr of electric motors, robotic arms spring into action.

Martyn Williams

Martyn WilliamsA robot controlled measuring probe sits in a vat of liquid as part of cellphone RF testing at UL in Fremont, California, on April 13, 2017.

At the end of each arm is a sensitive probe that measures the strength of the RF field at its tip.

“The probe is essentially a very small antenna,” Weaver said. “It dips into the liquid and measures the electric field strength in the liquid, and from there we can calculate the dose, how much energy is absorbed by the user.”

By using a liquid, the probe can be placed at varying distances from the cellphone under test so the field can be determined near the skin and deeper inside the body.

Martyn Williams

Martyn WilliamsA measuring probe sits in a vat of liquid as part of cellphone RF testing at UL in Fremont, California, on April 13, 2017.

The lab tests a range of products, including smartphones, laptops and wearable devices.

“A watch, for example, could take maybe a day, because there’s not much in it,” said Weaver. “A complex cellphone could be several weeks, using multiple systems at a time.”

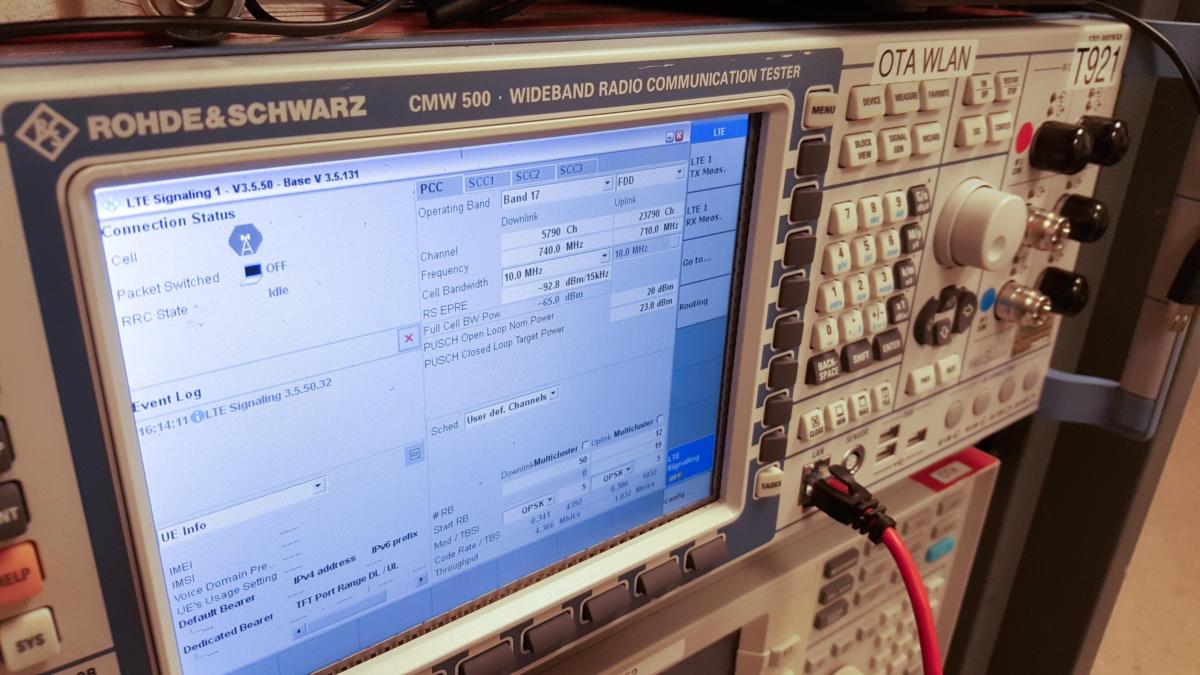

Whereas 15 years ago, a cellphone connected to just two or three frequency bands, today a phone like the iPhone 7 connects to more than 20 LTE bands, a handful of bands for older cellular technologies, two Wi-Fi bands and Bluetooth, so the testing takes a long time.

To generate these signals, a communications tester sits on a nearby shelf. It can imitate every wireless network the phone is likely to come into contact with and prompt the phone to generate signals of different strengths.

Martyn Williams

Martyn WilliamsA piece of measuring equipment used as part of cellphone RF testing at UL in Fremont, California, on April 13, 2017.

The result of all this work, hopefully, is an approval from UL that confirms the product is within SAR guidelines. The results are usually given on the safety and regulatory pages of manuals for the products — the bits that almost nobody reads. Apple has them grouped on a website.

The SAR limits are set in the U.S. by the Federal Communications Commission and in Europe by European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC).

This isn’t the only testing a phone must undergo before it hits the shelves. It needs to be checked to ensure it’s compatible with various cellular technologies and doesn’t cause interference to other users. Cellular carriers will often also put handsets through weeks of testing to make sure they work as advertised.