One mistaken click. That’s all it took for hackers aligned with the Russian state security service to gain access to Yahoo’s network and potentially the email messages and private information of as many as 500 million people.

The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation has been investigating the intrusion for two years, but it was only in late 2016 that the full scale of the hack became apparent. On Wednesday, the FBI indicted four people for the attack, two of whom are Russian spies.

Here’s how the FBI says they did it:

The hack began with a spear-phishing email sent in early 2014 to a Yahoo company employee. It’s unclear how many employees were targeted and how many emails were sent, but it only takes one person to click on a link, and it happened.

Once Aleksey Belan, a Latvian hacker hired by the Russian agents, started poking around the network, he looked for two prizes: Yahoo’s user database and the Account Management Tool, which is used to edit the database. He soon found them.

So he wouldn’t lose access, he installed a backdoor on a Yahoo server that would allow him access, and in December he stole a backup copy of Yahoo’s user database and transferred it to his own computer.

The database contained names, phone numbers, password challenge questions and answers and, crucially, password recovery emails and a cryptographic value unique to each account.

It’s those last two items that enabled Belan and fellow commercial hacker Karim Baratov to target and access the accounts of certain users requested by the Russian agents, Dmitry Dokuchaev and Igor Sushchin.

Martyn Williams

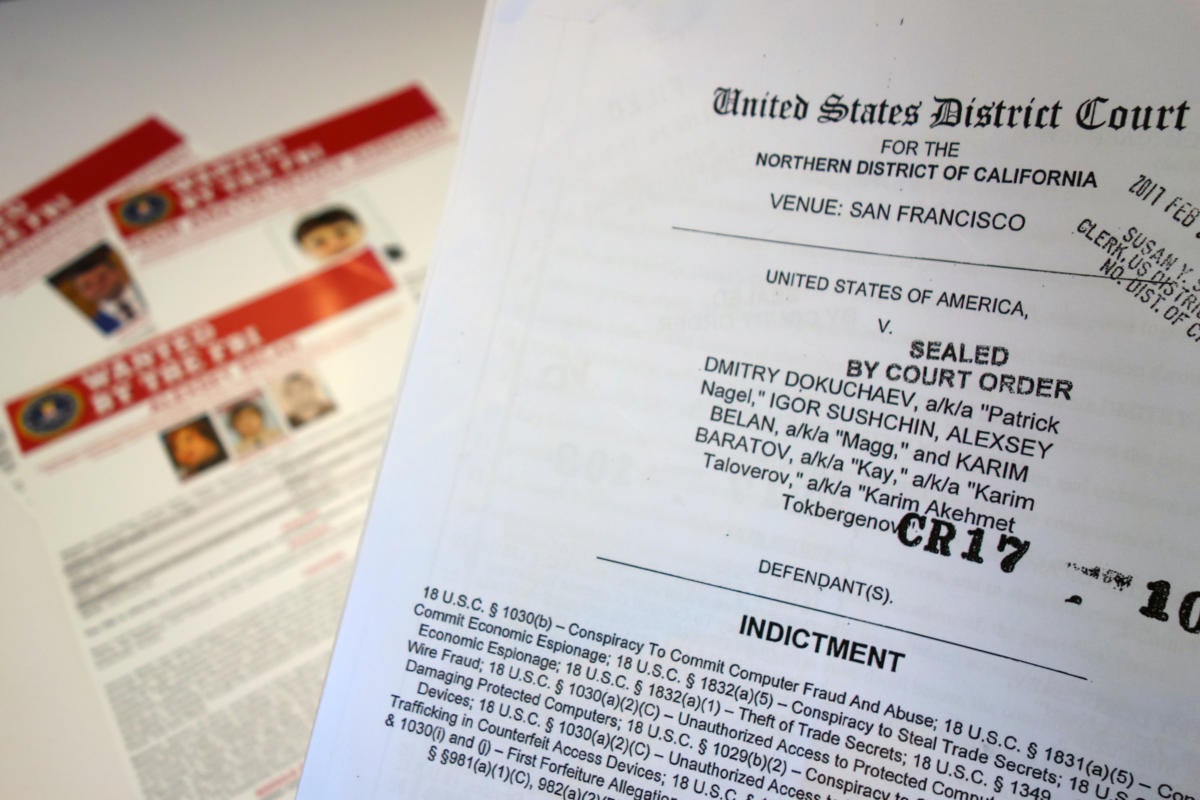

Martyn WilliamsA U.S. District Court endictment for four people accused of hacking Yahoo is seen against FBI wanted posters.

The account management tool didn’t allow for simple text searches of user names, so instead the hackers turned to recovery email addresses. Sometimes they were able to identify targets based on their recovery email address, and sometimes the email domain tipped them off that the account holder worked at a company or organization of interest.

Once the accounts had been identified, the hackers were able to use stolen cryptographic values called “nonces” to generate access cookies through a script that had been installed on a Yahoo server. Those cookies, which were generated many times throughout 2015 and 2016, gave the hackers free access to a user email account without the need for a password.

Throughout the process, Belan and his colleague were clinical in their approach. Of the roughly 500 million accounts they potentially had access to, they only generated cookies for about 6,500 accounts.

The hacked users included an assistant to the deputy chairman of Russia, an officer in Russia’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and a trainer working in Russia’s Ministry of Sports. Others belonged to Russian journalists, officials of states bordering Russia, U.S. government workers, an employee of a Swiss Bitcoin wallet company and a U.S. airline worker.

So clinical was the attack that when Yahoo first approached the FBI in 2014, it went with worries that 26 accounts had been targeted by hackers. It wasn’t until late August 2016 that the full scale of the breach began to become apparent and the FBI investigation significantly stepped up.

In December 2016, Yahoo went public with details of the breach and advised hundreds of millions of users to change their passwords.