Twilio’s CEO and co-founder, Jeff Lawson, is stepping down from his role and his seat on the company’s board, following months of pressure from activist investors and several quarters of slowing revenue growth. Khozema Shipchandler, Twilio’s president and a former GE denizen, is taking over as CEO.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Investors seem to be cheering the decision, with shares of Twilio up nearly 7% this morning, though they could also be happy that the company said it would report its fourth-quarter revenue, adjusted income and full-year adjusted income above its previous forecast.

While the timing of the move was a surprise, it’s not a massive shock to see Lawson heading for the exits. Investors have long made clear their discontent with Twilio’s recent performance, and at some point, either the results improve or something changes at the top. And while the company did raise its very modest forecast, this move may imply that its growth story did not improve as much as the board or activists wanted during the fourth quarter.

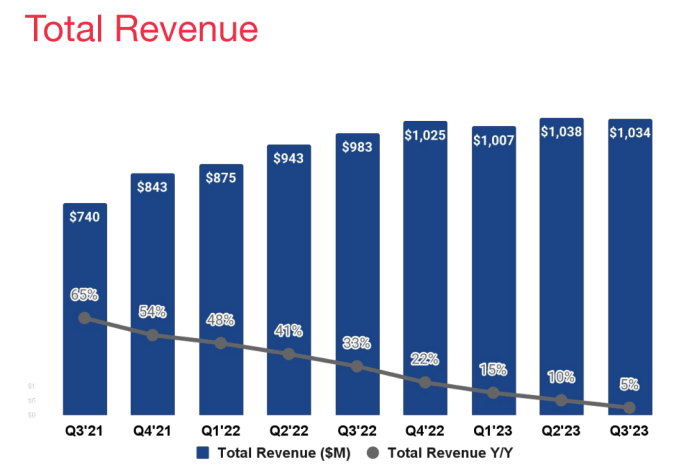

How is the company performing? In its third quarter, Twilio’s revenue increased 5% to $1.03 billion from a year earlier, and at the time, Lawson gave the results a positive rub in his official commentary, touting “another record quarter of non-GAAP income from operations and free cash flow.” Investors did not view the figures as favorably, though, and were seemingly more focused on the company’s anemic and slowing rate of revenue growth.

For the fourth quarter of 2023, Twilio projected that growth would slow even further, falling to 1% to 2%, though now with the company promising better results than expected, we’ll have to wait and see what it really managed as the year came to a close.

What does Lawson’s exit tell us?

A few things. First, activist pressure on companies is not something that can always be ameliorated by a board shakeup or smaller changes to operations. Second, we learned that while some tech companies have recently survived their time in the activist barrel with their CEO in place, that won’t always be the case.

I expect that the investors leaning on Twilio for change won’t take the leadership change, and the ensuing market reaction, as impetus to do less similar work in the future. Slow-growing software companies that remain unprofitable on a GAAP basis, take note: Here there be activists.

Another element that comes to mind is how fickle on-demand pricing can prove to be. If Salesforce is the godfather of the SaaS model, Twilio is the patron saint of on-demand pricing — charging its customers for how much of its telecom-focused software services they actually used through its API. What’s more, Twilio rode that business model to great heights.

The company’s stock peaked at more than $345 back in early 2021, but the downturn saw it start last year at around $50 per share. Today, Twilio stock is worth about $74 per share, accounting for the recent spike.

Partly driving those declines was a steady dip in revenue growth:

And that, in turn, was partially predicated on the following trend:

We can see that Twilio’s revenue growth has slowed in line with its dollar-based net expansion rate. In essence, Twilio’s rapid growth was heavily predicated on its customer base spending more on its products over time, but when that well ran dry — similar to how nearly every software company has been dealing with customers tightening spending — the company’s growth rate fell.

Brutal.

Still, I don’t think that we should consider these results to be Lawson’s legacy. Sure, the company has had a tough time lately, but that was just the final chapter of a very long book. Twilio did what it set out to do: Build a huge business, make its investors a mint, and multiply its worth after going public. That’s a grand slam in the world of startups.

I am also not convinced that the strategic moves that some of its activist investors want to see — more on that here — make much sense. So when we consider Lawson’s tenure, I think that the bulk of what’s happened is the real story, and the last few years are more a result of a hot company suffering in a suddenly colder economy.

That’s not to say that mistakes were not made. The company overhired, which led to successive staffing cuts that were painful, regular reminders of its struggles. You could also quibble about its cost base more generally, among other things. Still, this company enjoys run-rate revenue of $4 billion and generates lots of cash. That’s impressive, period.

Perhaps the lesson here is that the better a software business model is for customers, the more variable results will prove as the economy evolves. When the market was hot, Twilio grew like the proverbial weed and was handsomely rewarded by the stock market. But when the economy slowed, that picture turned upside down. A business model that charges for what you need is great when customers need and want more, but when enterprise clients are trying to find savings, your business will be less protected from those cost cuts than, say, a traditional SaaS company.