Image: Alex Campbell

Image: Alex Campbell

Taking back ownership of your data is rough. I’ve been trying to de-Google my life for almost a year, and I still haven’t mastered it. I still need my Google account and Gmail address to use my Android phone. I still use Google maps. And I still use Google Drive when I need to collaborate on documents. But I have managed to take back my personal files and sync capability.

It’s amazing how much we rely on cloud services today. Documents, contacts, photos, and more all live online in a way that is often transparent to the user. But what if you don’t want your data in a nondescript server farm that you have no control over? What if you don’t want a Silicon Valley company to have dystopian-level access to your digital life?

The alternative to entrusting your data to cloud providers, usually means forking over some money. If you want to go the home server route, you can build it around FreeNAS or OpenMediaVault. You can also spend a few hundred bucks for a network attached storage device from the likes of QNAP or Synology.

But there is a tool that can do a lot of the basic file-sync stuff on the hardware you already have for free: Syncthing.

Alex Campbell

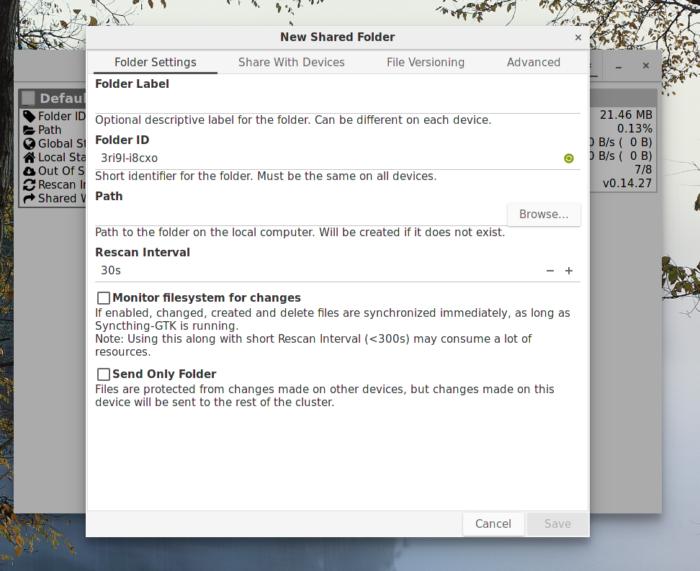

Alex CampbellManually setting up folders in Syncthing with the GTK GUI is pretty straightforward.

Sync for free (as in speech and beer)

As much as I believe in having a home server to keep precious files away from the public cloud, building or buying networked attached storage (NAS) can be costly and time-consuming. At minimum, you need a Raspberry Pi and a USB hard drive. At most, you’ll need an entire system: CPU, motherboard, the works. The open-source application Syncthing is free software (using the Mozilla 2.0 license) and doesn’t require any of that build time or financial investment.

Syncthing is a program that does just one thing: sync files. The way it works is pretty simple, and at first glance isn’t much different than Dropbox or Google Drive. First, you have to set up the client on the devices you want to sync. When those devices are online at the same time, Syncthing will sync the files between them.

Unlike cloud storage, Syncthing does not store data on a central server. (Well it can, but more on this later.) The sync occurs directly between clients through an encrypted tunnel. Additionally, Syncthing does not require you to sign in to a service or pay a fee.

How to set it up

Syncthing is fairly easy to set up and can be found in most software repositories. Syncthing is primarily a console application, so if you’re using it on a laptop or desktop, you’ll probably want to install syncthing-gtk, which provides a GUI. The syncthing-gtk README page on GitHub has links to packages and repositories maintained by third parties. Syncthing hosts an apt repository for Debian and Ubuntu users, too.

Alex Campbell

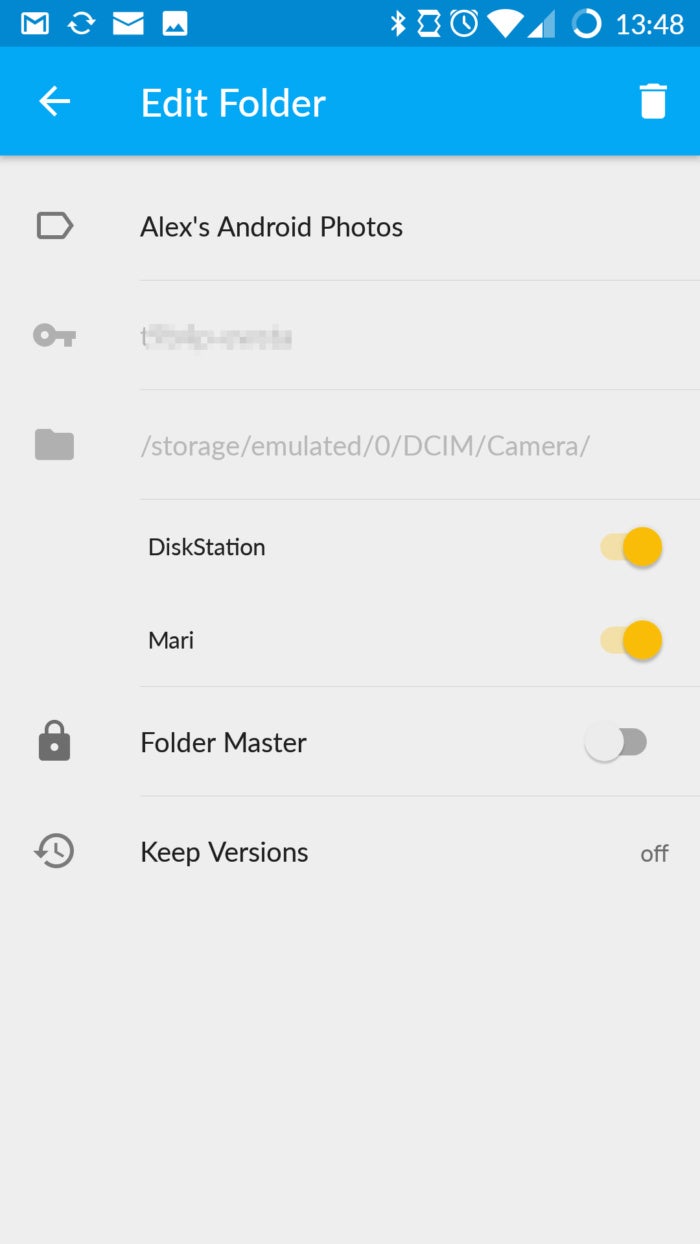

Alex CampbellThe Syncthing interface on Android is probably the easiest way to share folders between systems since it uses QR codes to add devices to your cluster.

Syncthing also has Android applications available through the Google Play Store or F-Droid. I’ve found that Syncthing is a great way to back up your Android photos without using a service like Google Photos or Flickr.

Once you’ve got the application installed, read through Syncthing’s Getting Started guide. The documentation team at Syncthing created a very in-depth how-to for first-time users, and have a lot of reference material to customize your own setup.

You might want a server anyway

Having Syncthing sync files between two machines is great, but having a server is even better. While Syncthing does not require a server, running even a small Raspberry Pi server with a USB HDD attached can speed up the sync process and give you a little more peace of mind. It also frees you up from having to make sure that at least two of your devices are online at the same time since servers are generally always on

Syncthing is a bit similar to the closed-source Bittorrent Sync in that the more devices that are online and sending pieces of files (called “blocks”) to one another, the faster the sync works. Say you’re trying to sync files to your phone while you’re at lunch. By having both a server and your PC online syncing files, your phone can download the files from two machines instead of just one. (This is analogous to downloading a file from multiple peers using Bittorrent as opposed to using a single peer.)

Syncthing also allows versioning for shared folders, which is ideal for a server. File versioning saves versions of a file to a backup folder automatically. If you change a file on one node in your Syncthing cluster, another machine that has versioning enabled will back up its current version before downloading the changed file. Versioning can also protect files from deletion since a deletion is considered a change. While the file will disappear from the sync folder, the versioned files in the backup folder will remain. You can also change the number of versions to save, as well as the methodology.

It’s not too hard to build a small server on the cheap, and there are many ways to go about doing it. Once you have a server, you can install Syncthing from a repository or via Docker if you prefer. I have a Synology DiskStation NAS at home, so I set up my Syncthing server on the Synology using a package from the Synocommunity repository.