Image: Nvidia

Image: Nvidia

Let’s say you’ve just bought one of Nvidia’s slick new Pascal-based GeForce graphics cards such as the GTX 1070, and now you’re seeking a G-Sync monitor to go with it.

Looking at what’s available, you’ll probably become envious of PC gamers on the Radeon side of the fence. Compared to G-Sync monitors, displays supporting AMD’s FreeSync adaptive sync tech are generally much cheaper, with a wider range of vendors and tech specs to choose from. The website 144HzMonitors lists 20 available G-Sync monitors, versus 85 FreeSync monitors, the latter showing more combinations of screen size, refresh rate, and resolution.

Why the disparity? The conventional wisdom is that Nvidia’s proprietary G-Sync hardware module raises the monitor price due to licensing fees, but that’s not a satisfying explanation. Nvidia is still far and away the market share leader in graphics cards, so you’d think that most monitor makers would create G-Sync variants of their FreeSync displays and at least give GeForce users the option of absorbing the module cost.

As I started talking to monitor makers, a more complicated picture emerged. The real reason for G-Sync’s limited availability is as much about design and development concerns as it is about the price of the module itself.

G-Sync vs. FreeSync refresher

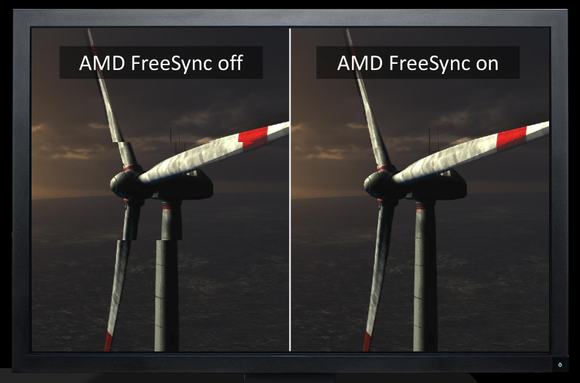

PCWorld has already published a detailed primer on G-Sync and FreeSync, but the gist is that both technologies allow the graphics card to adjust the monitor’s refresh rate on the fly, matching it to the PC’s current framerate. This prevents the screen tearing effect that occurs when refresh rate and framerate fall out of sync, and (mostly) eliminates stutter, creating a buttery-smooth gameplay experience.

G-Sync accomplishes these variable refresh rates with a proprietary hardware module, which is built into every supported monitor. With FreeSync, no such module is required, because it uses the variable refresh rate tech that’s part of the DisplayPort standard (and, more recently, HDMI as well). But again, the lack of extra hardware is not the only reason FreeSync monitors are cheaper and more readily available.

Design costs

Some display makers say Nvidia’s module requires more room inside the monitor enclosure. While that may not seem like a big deal, creating a custom product design for one type of monitor raises development costs considerably, says Minhee Kim, a leader of LG’s PC and monitor marketing and communications. By comparison, Kim says, AMD’s approach is more open, in that monitor makers can include the technology in their existing designs.

“Set makers could adopt their technology at much cheaper cost with no need to change design,” Kim says. “This makes it easier to spread models not only for serious gaming monitors but also for mid-range models.”

LG’s FreeSync monitor selection bears this out: The company offers several 1080p monitors under 30 inches diagonal with an ultrawide 21:9 aspect ratio, priced as little as $279. With G-Sync, the only 1080p ultrawide monitor is a 35-inch curved panel from Acer with a much higher refresh rate. The cost? $900.

The cheapest ultrawide 1080p G-Sync monitor will set you back nearly $1000.

Even if monitor makers proceed with the necessary research and development, the resulting product will be more expensive, which inevitably means it will sell in lower volumes. That, in turn, means it’s harder for monitor makers to recoup those up-front development costs, says Jeffry Pettinga, the sales director for monitor maker Iiyama.

“You might think, oh 10,000 sales, that’s a nice number. But maybe as a manufacturer you need 100,000 units to pay back the development costs,” Pettinga says.

Meanwhile, he says, monitors are constantly improving in other areas such as bezel size. As monitors shrink from wide bezels to slim bezels to edge-to-edge displays, the risk is that a slow-selling G-Sync will become outdated long before the investment pays off.

“Let’s say you introduced, last year, your product with G-Sync. Six months of development, and you have to change the panel. You haven’t paid off your development cost,” Pettinga says. “There’s a lot of things going on on the panel side.”

Limited flexibility

Costs aside, some monitor makers feel restricted in how they can differentiate their G-Sync monitors.

Display maker Eizo, for instance, has a feature in its gaming monitors called Smart Insight that adjusts gamma and brightness on the fly, helping to improve visibility in light and dark areas. This feature wouldn’t be possible with G-Sync, says Keisuke Akiba, Eizo’s product & marketing manager, because Nvidia’s module handles all the color adjustments itself.

“The G-Sync module accepts color adjustment in the module, not an outside chip,” Akiba says. “Our color adjustment needs power and flexibility so we’ve gone for FreeSync.”

G-Sync doesn’t allow monitor makers to offer their own color adjustments, like Eizo does.

Monitor makers also have limits on what video inputs they can include. All G-Sync monitors have one DisplayPort input, and in some cases they also include an HDMI input that doesn’t support variable refresh rate. You won’t find any G-Sync monitors with more than two inputs (or with support for DVI). Also, G-Sync doesn’t support variable refresh rate over HDMI. That means every G-Sync monitor must include DisplayPort—again raising the cost to manufacture.

“DisplayPort is relatively expensive on a monitor because of the cable—it’s a quite expensive cable if you include a cable—and the board design itself. So DisplayPort adds a lot more to the cost than HDMI,” Pettinga says.

Nvidia’s answer: It’s about value, not cost

In an interview, Tom Petersen, Nvidia’s director of technical marketing, doesn’t dispute any of these concerns, and acknowledges that the high cost to develop G-Sync monitors puts them into a pricier segment of the market.

But to Nvidia, that’s okay, because G-Sync is supposed to be a premium product. The company points to several ways in which G-Sync is superior to FreeSync, including its ability to handle any drop in refresh rate—FreeSync only works within a specified range—and Nvidia’s complete control over things like monitor color and motion blur, which Petersen argues are superior to what monitor makers are offering outside the module.

For those reasons, Petersen says any price disparity between comparable G-Sync and FreeSync monitors is not due to the module, whose cost he says is “relatively minor,” but due to monitor makers’ decision to charge more.

“To me, when I look out and see G-Sync monitors priced higher, that’s more of an indication of value rather than cost,” he says. “Because at the end of the day, especially these monitors at the higher segments, the cost of the components don’t directly drive the price.”

Nvidia says the proprietary module is not a major contributor to the cost of G-Sync monitors, especially since it replaces some other standard components.

Perhaps that’s a fair point for higher-priced monitors, but as we’ve heard from monitor makers, the bigger issue is that the module is inherently harder to include in lower-priced options. With G-Sync, for instance, you can’t buy a 60Hz monitor in less than 4K resolution, whereas FreeSync offers plenty of options in 1440p and 1080p.

Nvidia’s Petersen suggested that addressing these mid-tier markets isn’t a priority. “I think over time, you’ll see lower-priced monitors that are lower-featured, that include G-Sync, but it’s not our goal,” Petersen says. “Our goal is to provide a premium gaming experience, and the premium gaming experience requires a lot of hands-on work from Nvidia, and that’s where we’re going to continue to focus over time.”

Of course, some monitor makers would prefer that Nvidia supported DisplayPort’s adaptive sync standard, so users could ,at least enjoy some anti-tearing benefits even if they didn’t splurge for a G-Sync monitor. To that, Petersen says “never say never,” but right now he argues there’s no benefit to doing so.

“I’m worried that by just throwing it out there, we could be delivering the same less-than-awesome experience that FreeSync does today,” he says, “and that’s just not our strategy.”

For loyal Nvidia customers, the takeaway is clear: If you want G-Sync, be prepared to jump into the deep end of luxury gaming monitors, because the technology isn’t going downmarket anytime soon.