Image: Alex Campbell

Image: Alex Campbell

There are plenty of nerdy things to love about using Linux, but one of the nerdiest things has to be the use of the text-mode web browser. And it’s awesome.

I can feel you backing away slowly. Others might be thinking, “Alex, it’s 2017. Why on earth would I use a text-mode browser? What are you, stuck in 1985?” Hear me out: The text-mode web browser is one of those super-useful tools that can really save your bacon.

I always make a point of installing a text-mode browser like Links just in case I need it. Since I’m one of those people who like to break my Linux installation experiment with things, I’ve had to turn to Links more than once.

Links to the rescue

Just about everyone has been there: Something goes wrong with your PC, so you search the ol’ Google machine looking for answers. New Linux users probably do this more often than anyone else, since there are a lot of new things to learn.

Alex Campbell

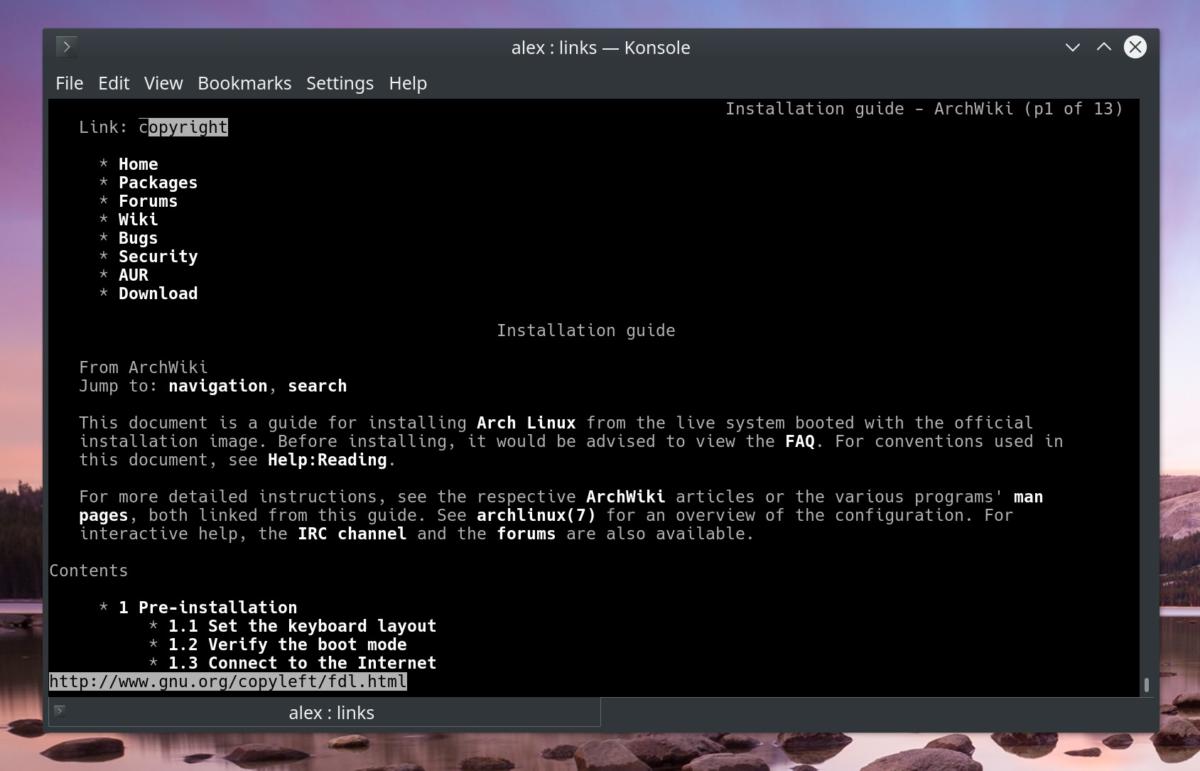

Alex CampbellA text-mode browser like Links comes in handy when you don’t have a working graphical environment.

Sometimes things go wrong. Sometimes, a desktop environment hangs or fails to load, kicking the hapless user into the darkness of the text-based TTY console. If the user is without a second PC, left her cell phone at home, and doesn’t have a live USB drive with her, how should she fix things?

In this instance, some people may turn to manual pages for help. While manual pages are good for finding out how to do things, they aren’t much help when you’re looking to fix something that went awry. Sometimes looking online is the best way to fix a problem. To look online, you need a browser, unless you feel like reading HTML page by page after downloading documents with other tools.

I should note that Links can be run in a graphical mode if you want, by running links with links -g. However, the graphical mode will require starting a display server like X. If you really need Links because your X.org configuration is messed up, it doesn’t make much sense to start it in graphical mode.

What Links offers

Links functions like most of the browsers you’re used to, with a few changes. First, there is (obviously) no mouse input (unless the gpm daemon is running), no images, and no Flash. Besides some rudimentary styling, a webpage’s CSS (the code that tells your browser how to lay out the page and what colors to use) is largely ignored. What you get is a text document that is long (especially when a page has lots of nested menus), but ultimately readable.

There’s a big advantage to having everything but the bare-bones HTML represented: Pages load lightning-fast.

Alex Campbell

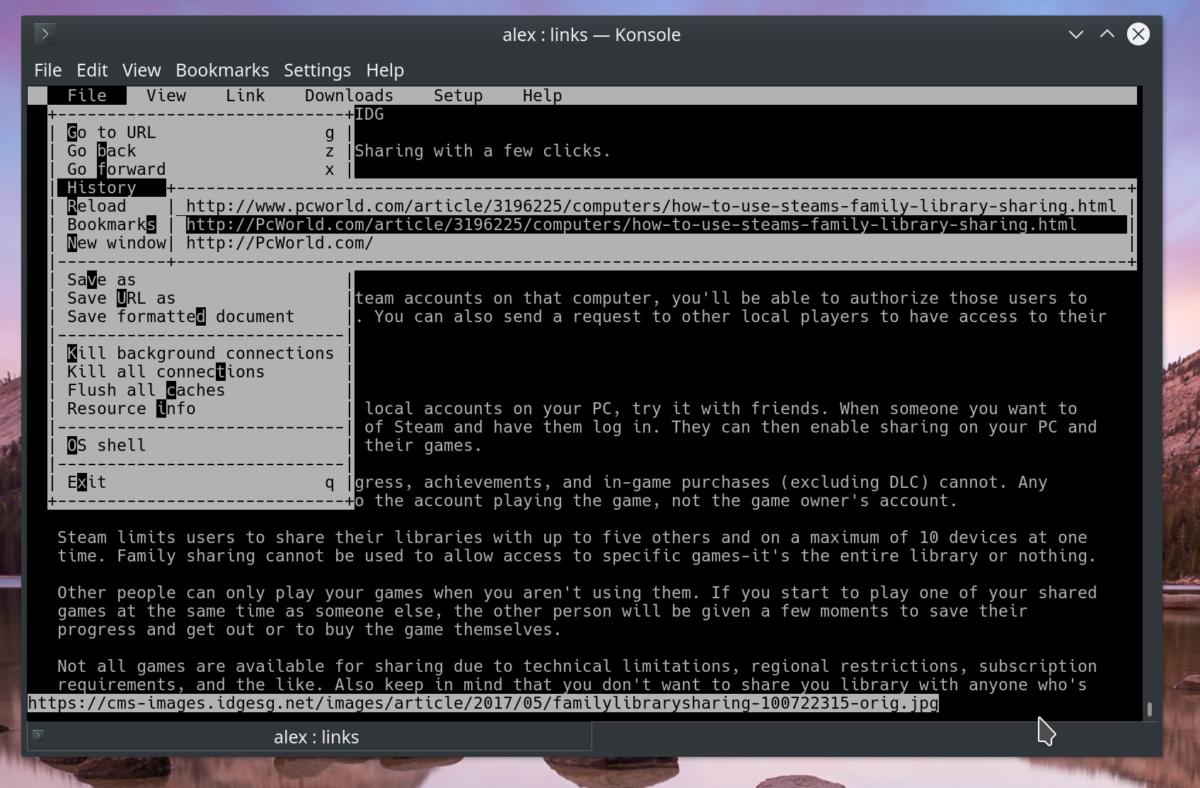

Alex CampbellLinks has features you’d expect from a graphical browser including history, text search, download management, and bookmarking.

Links has a lot of the features you’d expect in a graphical browser like Chrome or Firefox, as well. You can bookmark pages, search for text within a page, and even access your history.

Links is really simple to use too. To use Links, simply type links <url> on the command line. Once Links is open, you can use keyboard shortcuts to navigate a page or perform operations. The up and down arrow keys move the caret from one link to the next. The right-arrow key “clicks” on links (you can also use the Enter key), while the left-arrow key functions like your back button. Other shortcuts are shown in the menu, which can be opened by hitting the Escape key.

Links is available in pretty much every repository that I can think of and should be near the top of your list of packages to install on a new system. You never know when tinkering or a corrupted configuration file might kick you back into the stone ages of computing like Ash in Army of Darkness. You might as well bring along a boomstick. Or your smartphone.